Eleven years ago, on March 15, 2011, protests broke out in Syria against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. Over the following years, a revolution took place, wresting much of the country from Assad’s control. Yet as governments around the world intervened to support various factions, the struggle became more and more violent, culminating with the rise of the Islamic State, on one side, while the Russian government stepped in on the other side to enable Assad retain power at a tremendous cost in human lives. Millions of Syrians were forced to flee.

In Paris, some exiles from the Syrian Revolution founded the Syrian Cantina, a community center providing a space for social movements and organizing events to bring together revolutionaries and grassroots organizers from around the world. In the following interview, the participants recount how they were politicized in the course of the revolution, describe the challenges of becoming organizers in a new country, and analyze the roots of a false “anti-imperialism” that silences the voices of the people whose interests it claims to defend. As millions are driven into exile from Afghanistan and Ukraine to Sudan and Haiti, this is an invaluable document about how refugees can continue their organizing in new contexts, how locals can help to make this possible, and the meaning of international solidarity.

Lunchtime at the Maison Ouverte (the open house), the first space that hosted the Syrian Cantina.

First, introduce the Syrian Cantina.

L—: Some of us met in an occupation of the Paris 8 University in 2018, demanding the collective regularization of undocumented immigrants who were living on the streets that winter. Some of us helped with Arabic translation, some with cooking, others with mediation and negotiations. That was the first decisive encounter between some of the French and Syrian people who are now members of the Cantina.

A few months later, there were more university occupations: some focusing on refugee struggles, others on student struggles. With a group of Syrian students, we thought that we had to intervene in the student movement and not restrict our activism to refugee issues. We began doing interventions in occupied campuses to talk about the mobilization of students in Syria during the revolution. This allowed more encounters and links with the “radical left” circles in the Parisian region.

In late 2018, the Yellow Vests movement erupted; both Syrian people and French people who went on to become members of the Cantina participated. The following March, some comrades who were involved in the Yellow Vests of Montreuil invited us to speak on the anniversary of the Syrian Revolution about self-organization and the lessons we could share from our experiences for the uprising that was taking place. It became clear for us that we wanted to organize in Montreuil, especially as we were finishing our studies and wanted to continue our political activity beyond the student movement and refugee struggles.

The Syrian Cantina was born out of our desire to create a space for refugee self-organization and the need to recreate a sense of “home” for us in France.

The Syrian Canteen contributes a dinner to the first anniversary of the Yellow Vests movement.

D—: We wanted to continue the revolution, to continue our path pursuing our goals from the Syrian revolution. We don’t want to resign ourselves, to stay calm and quiet once in exile. In France, it is possible to do many things, there are many political movements and communities that we can organize and share experiences with in order to build solidarity and prove that freedom is possible. People in France have a lot of experience in revolutionary activities. Also, we wanted to show that there is an alternative to both Assad and the Islamists.

L—: We cook three times a week and share our culinary heritage—through cooking lessons, for example. At the same time, we organize concerts, film screenings, expositions, and the like. The idea was to articulate connections between different spheres: a cultural space for mutual aid and transnational solidarity. And so we have language classes in Arabic and French. We also organize discussions regularly—for example, about the links between the Syrian and Palestinian struggles, or the recent mobilizations in Sudan against the military coup, or encounters with exiled comrades from Afghanistan to inform us about the situation there. All of our activities are free or pay-what-you-can. Lastly, we have two major annual events: one is the anniversary of the Syrian revolution and the other is our internationalist festival, “The People Want,” where we invite comrades from all over the world. At the last one, in November 2021, participants came from India, Chile, Greece, Iran, Sudan, Lebanon, and the United States. We discussed the potential of international feminism, debated old and new forms of internationalism, and compared revolutionary hypotheses. We are currently preparing the fourth one.

We are based in a self-organized social center called the AERI [Ateliers d’expérimentations révolutionnaires et imaginaires, “Workshop for revolutionary and imaginary experimentation”]. It is a space for solidarity and mutual aid involving dozens of other collectives and activities. People from many different nationalities and backgrounds meet and organize in this space. Everything is either free or pay-what-you-can. There are activities like yoga or feminist martial arts, 3D printing and coding workshops, a bakery, photo lab, and a lot more. Of course, there are also collectives such as the Yellow Vests, who have a canteen of their own, and the Popular Solidarity Brigades, who were very active in mutual aid work during the lockdown. It suits us well to be in the midst of this diversity of practices and approaches; this space gives us the opportunity to anchor ourselves and our work in the active and rebellious territory of Montreuil and to contribute to the construction of local autonomy here. It also gives us the opportunity to meet a wide range of people, from neighbors who have no relationship to any political community but are curious to discover the space to political activists involved in struggles related to migration or housing.

A concert at the AERI space.

On a regular basis, we also organize events with French collectives or refugees/exiled activists in France. Last year, we were at the ZAD in Sacaly and the Longo Mai farm in the south. Finally, we work with different collectives and groups internationally: we have started building a small network thanks to our annual internationalist festival.

This is how we met and started working together.

One of my dreams is to participate in the creation of some kind of movement from below for the self-organization of refugees. Not only Syrians in France, but other nationalities—and, why not, on the scale of Europe, to get started. Like an international of exiled persons!

D—: One day, we would like to see the Cantina inside a free Syria. For now, a Syrian Cantina has just started in Luxembourg. We are so happy and proud that our project was able to inspire people in another country. We hope that more Syrian Cantinas will flourish all around the world!

L—: The next time there will be a popular uprising in Syria, we hope that our work will contribute to lessening the world’s indifference, so that the abandonment that Syria suffered from 2011 on will never recur again.

What were your experiences with politics in Syria before the uprising?

L—: When the first protests broke out, I was 18 years old. I don’t think I would have been politically active the way I am today if it wasn’t for the Syrian Revolution. Before the revolution, I used to say that I hated politics; I saw it exclusively in the form of state politics, and as such it was full of lies and deceit. Politics in Syria before the revolution was almost exclusively the domain of the government. Additionally, the regime’s propaganda and surveillance were everywhere, inescapable. We had to endure it from very early on in primary school (where we were all forced to be members of the Ba’ath Party). I wanted to rebel against what I perceived to be authoritarian, though I wasn’t capable of naming it as such at the time. To me, it was more like a style, or an instinctive refusal of the highly punitive and incompetent authority that we had to deal with in school and in society at large. At 17 years old, I was kicked out of high school after I had an argument with the “nationalism” teacher. The next day, the school’s principal told me that some of my classmates’ parents had called to say that I was disturbing their kids’ education. My lower-middle-class family was politicized, but I only really understood that after the revolution.

D—: I worked in the sports field. I was a coach at first, then I started doing coordinating and office work for different missions: the Arab women’s sports association and the Syrian women’s football association. I had a clandestine engagement in a political party in the 1980s.

A—: In the 1980s, if you were involved in any kind of political activity outside what the government allowed in the framework of the single party, or if you wanted to disobey the party line, you had no right to a normal life. My father was active in a leftist movement. Because of his activities, both of my parents had a hard time finding work. I started going to the meetings of the party that my father was involved in. I also participated in round tables and in the organization of demonstrations in support of Arab countries. We protested in support of Palestine and then Iraq, since these were the only demonstrations that we were allowed to hold. During the demonstrations, we chanted slogans against Arab heads of state, but these were also partly addressed to the regime. Although the party I was involved in became public, many militant activities had to remain clandestine. At the university, it was very difficult to be politically active; student unions were controlled by the regime and highly surveilled.

R—: Like many Syrians before the outbreak of the revolution, my activities were limited to timid criticism of the regime in the private space of the family. My father is a former opponent of the regime; I grew up surrounded by former communist activists and former prisoners.

I quickly realized that people would be risking their lives if they got involved in politics, given the surveillance and repression. When I first learned about the Hama Massacre, which occurred in February 1982, ordered by Hafez al-Assad, I was nine years old. I saw old bullet marks on the wall of Hama and asked my father about them and he told me the story. The next day at primary school, as usual we had to venerate Hafez al-Assad with some slogans. I was so upset that I told my friend from Hama that she should not sing the propaganda chants because of the massacre that Hafez had committed in her city. A few hours later, my friend’s father called my father and asked him to keep me silent. People were afraid of each other.

Stories of repression, prison, and massacre have fed a deep hatred towards any authority that reduces life to its basic dimensions (work, eat, sleep) and annihilates all creative and critical thinking.

Graffiti in Syria in December 2012: “It’s almost here!!!”

What were your vantage points on the Syrian revolution?

L—: I remember when protests started in Tunisia and Egypt, I could not even conceive of the possibility of an uprising taking place in Syria. I thought to myself and told my friends: the risks are too high. Well, the price was too high, but a revolution did take place in Syria. In the very first months, some friends were arrested and tortured and had to leave the country. I was not involved in organizing, I was too afraid to end up in jail… rape is a common method in Assad’s prisons.

A—: I participated in the demonstrations in Douma, a suburb of Damascus. In April, when I returned to my hometown, I was questioned by the police and then released. At first, they didn’t arrest many people who were in political parties like me. I think it was a strategy to figure out who the people who were organizing the protests were. Then I was blacklisted by the regime and kicked out of university. I went to Aleppo and joined the struggle there clandestinely. I did documentation and humanitarian work.

D—: I was very proud at the start of this revolution. I had so much gratitude and respect for the children of Daraa, who were among the first to demand the fall of the regime and who finally changed the history of the country. I participated with many athletes in showing the ugliness of the regime by forming a group called the Free Syrian Athletes Association. We were able to write to the International Federation and provide it with pictures and documents showing how the regime was pressuring well-known popular athletes and trying to instrumentalize them to delegitimize and suppress the demonstrations.

The regime made the Abbasieen Stadium in Damascus into a military base. We heard terrible stories about repression taking place there. The regime wanted to change the identity of places as much as the identity of individuals.

If we go back to the basic principles of Olympic sports, we find peace and reconciliation. We find the rejection of discrimination. With the Free Syrian Athletes Association, we succeeded in preventing the representatives of the Syrian Olympic Committee from participating in the International Olympic Committee conference, on account of their violating the Olympic Games Charter.

I think that revolution is a way of life in which we strive for what is fair against everything that has become outdated, everything that has been proven to be dysfunctional, no longer valid. It is a means to achieve more justice so that we can live in a more beautiful world. The Syrian Revolution was a necessity, it is a local cry from one of the oldest inhabited capitals in history against tyranny and all forms of dictatorship.

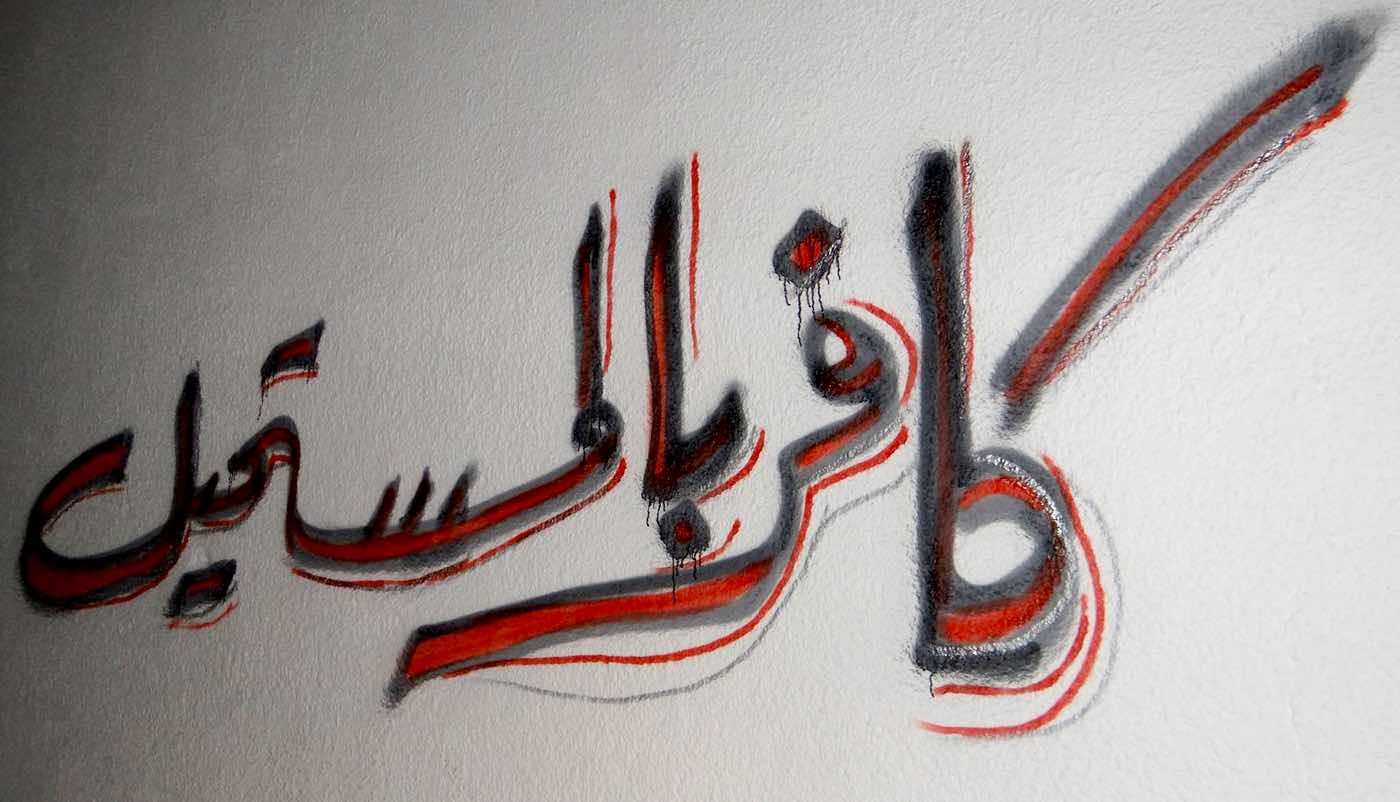

Graffiti in Syria in October 2012: “Unbeliever in the impossible.”

R—: When the uprisings started to spread in the Arab world, we stayed nailed to the television watching the news. Their cause was ours. We shared the same experience of life under different repressive regimes. I still remember my family shedding tears when the first demonstration took place in March in Syria. We would have never thought it was possible.

A process of coordination and organization of the movement progressively emerged on several levels.

I was 16 years old at the time, and with a bunch of friends, we took it upon ourselves to organize demonstrations, drawing graffiti and slogans on the walls, at the high school level. We skipped classes in order to go and inform people orally about the holding of a demonstration at such a place and such a time, avoiding using the telephone and other means of communication that could be monitored.

What was remarkable during the revolution was the return of emphasis on the local scale, its particularities and its influence. The names of small districts and small towns came back to the detriment of the vast agglomerations. An uprising from below was taking place while Syrians had never been so united.

For more on the Syrian revolution, we recommend the following books:

- Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War, by Leila al-Shami and Robin Yassin-Kassab

- The Syrian Revolution: Between the Politics of Life and the Geopolitics of Death, by Yasser Munif

- The Impossible Revolution: Making Sense of the Syrian Tragedy, by Yassin al-Haj Saleh

Graffiti in Syria in July 2012: “Freedom.”

Why did you ultimately have to flee Syria? What was your experience like as refugees?

D—: The decision to flee became inevitable, especially after I received a direct threat ordering me to remain silent and abandon all organizing activities. I felt that I was in danger and I was concerned about the safety of the only daughter I had. So I left.

A—: In 2013, with Da’esh entering the conflict, I had two choices, either taking up arms or leaving, so I left.

L—: I had to flee because my family decided that it was no longer safe for us to remain. I tried to convince myself that I was able to live in Syria even if my close family members left, but it was not very reasonable.

I remember that I spent half of my asylum interview with the French immigration authorities holding back tears. It was so exhausting to have to prove to people who had probably never set foot in my country, who probably knew nothing about the revolution and who didn’t give a fuck about emancipation in our region that I actually came from the place I come from, and that I would be in danger if I were to return to that place.

That was 2015. Friends even recommended that I take pictures with “known figures of the Syrian Revolution’’ in order to prove to the French authorities that the Assad regime considered me to be “dangerous” and, as such, “qualified” for refugee status.

My experience as a refugee is the result of state bureaucracy and discrimination; it is an experience of loss and deracination. There is one moment that I will never forget. When you seek asylum in France, you receive a letter to inform you that your passport (which you had to submit to the government as proof of your nationality) is conserved in the immigration office “archive.” When I got that letter, I imagined a really big hall with passports just packed one beside the other. I wonder what the hell they do with all of them?

Anyway, this is by no means novel—but beyond the Kafkaesque, humiliating, and racist administrative process, in which you spend the night outside waiting in line hoping to get an appointment in the morning, while cops yell at you and threaten to send you “back to the camps” if you don’t stand correctly in line… beyond all that, it is always important to remember that asking for asylum means letting a state decide whether you have the right to exist in a given part of the world. I urge people who experience seeking asylum to reflect not only on borders but also on the state as an institution that grants itself ridiculous prerogatives.

All the same, I did not have to walk nor take the sea to reach France. The people who had to do those things have more horrifying stories to tell.

Still, let’s be clear, Syrian refugees in France and other places in Europe are more or less “privileged” in comparison to other nationalities and skin colors. Access to refugee status was easier for Syrians than for people coming from Chad, Ethiopia, Sudan, Afghanistan, and other places. Again, this is a consequence of the state’s power to determine which places you have the right to flee from and which places are considered not to “represent sufficient danger.” Which is just absurd!

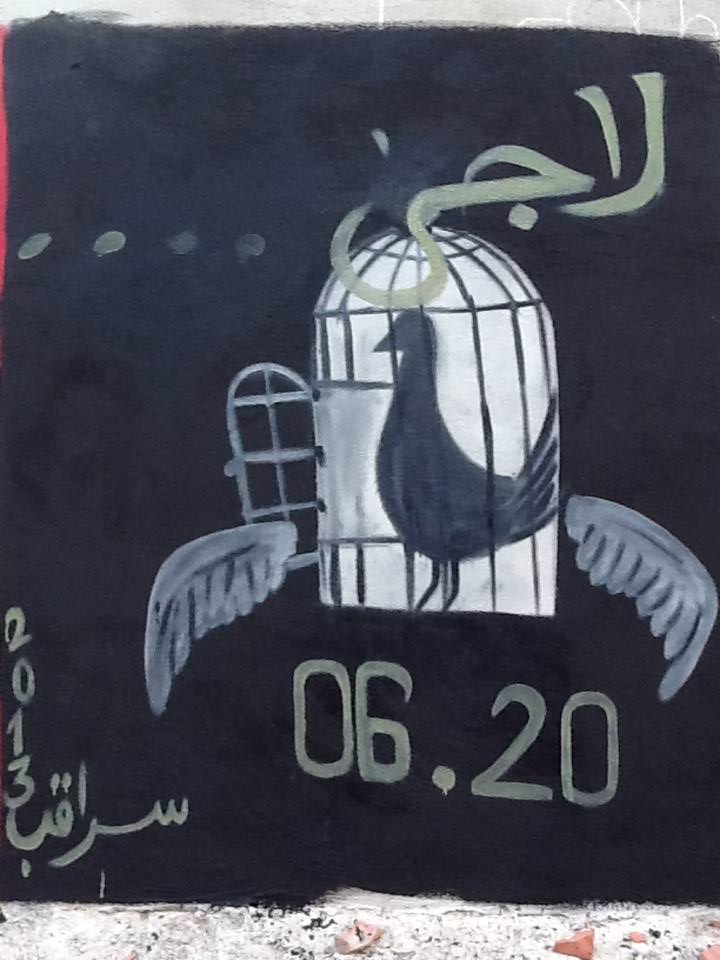

Graffiti in Syria in June 2013: “Refugee.”

When you arrived in France, what did you find there? How much did French political communities understand what was happening in Syria?

L—: At the beginning, when we started the Cantina, some people came up asking “What can we do to help the Syrian refugees? I can bring clothes!”—although we said very clearly that we were creating a popular cantina in the neighborhood. It was difficult for people to conceive Syrian refugees as actors who can express solidarity, not simply as those who receive it.

In France, I found a very vibrant militant scene, especially after 2016 and the mobilization against the labor law. It is different today; I think the French radical groups are at a low ebb now after the explosion of the Yellow Vest movement, which benefited immensely from autonomous, anarchist, and anti-authoritarian circles but ultimately posed very serious questions—even impasses—in relation to organization and strategy in social movements. Repression was quite serious. Today, other hypotheses are needed to take back the streets in a way that can threaten the government.

What is impressive to see in France beyond the insurrectional side of radical circles is the communalist movements: whether that is the different ZADs [Zone à Défendre, or Zone to Defend”] or different local projects and initiatives in active and politicized territories all over France. We were inspired by a popular canteen in Paris, la cantine des pyrénées. A few of us were used to cooking there and one member of the Syrian cantina used to take French classes there and help out with cooking. It is a wonderful place and each neighborhood needs a solidarity place like this one, so we created our project in Montreuil.

We learned a lot from French activists: the liberty they have allows them to think and practice things that were unimaginable to us before the revolution. For some of us, being in France was the first time we were exposed to anarchist or anti-authoritarian literature and ideas. Of course, some Syrians who were involved in self-organization did not necessarily call what they were doing by this name. Speaking with comrades here in France, we realized that what we were doing in Syria was what autonomous movements dreamed of doing in France. There was a period of time during which we had to harmonize our understandings of what we fight for and what we want. At some point, we managed to arrive at this: the local councils in Syria as a modern form of the Paris Commune.

Now let’s speak of the less positive aspects.

Most people sympathized with Syrians, having in mind images of killed children and destroyed buildings. For a period of time, I would avoid saying that I came from Syria, because sometimes that triggered a sort of “Oh, you poor girl” reaction. When you hear that regularly, it really becomes annoying.

Most political communities, especially at the early stages of the revolution, understood that there was a peaceful mobilization happening in Syria and supported it. Some radical circles had a problem calling that a revolution, though, because the protests did not immediately overthrow the regime and the demands for free elections or representative democracy were not perceived as sufficiently revolutionary (as people in France knew very little about the quasi-totalitarian situation in Syria), or else because the movement did not involve an anti-capitalist dimension. To put it simply, the revolution was “impure” and had no single defined narrative. Some militant leftists, in the confused 21st century, still want the sort of popular uprising that would resemble the sanitized versions they have read in theory or history books.

Anyway, in the early years of the revolution, people seemed to understand that it was not crazy Islamist terrorists on the streets of Syria. Yet they could not perceive these people as potential comrades. Most people who were on the streets were not anarchists: but where are anarchists a majority in any popular nationwide uprising?

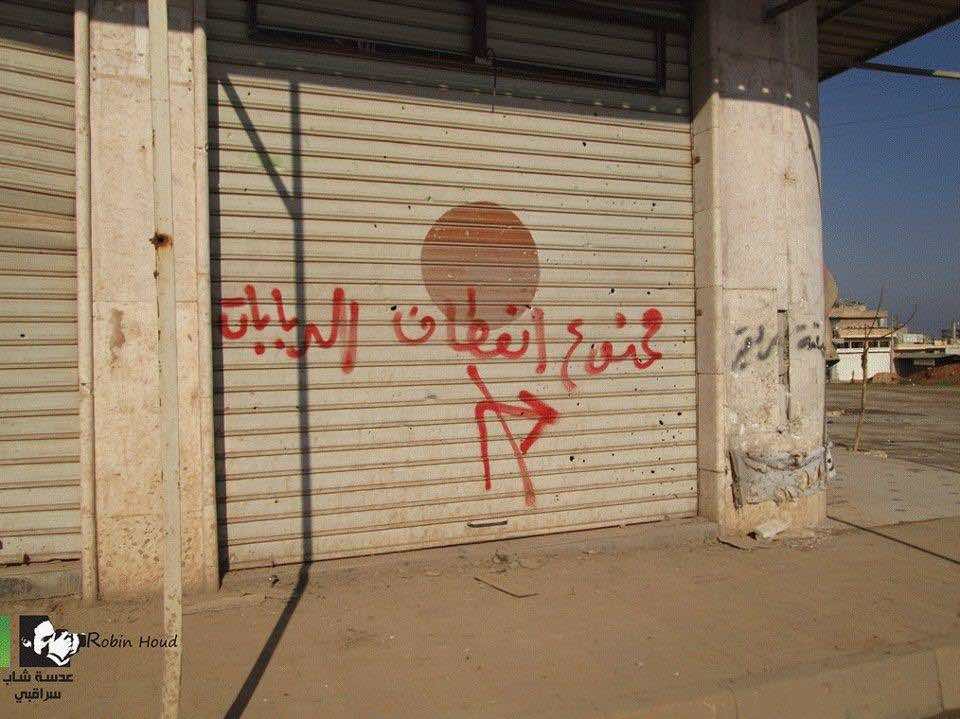

Graffiti in Syria in December 2012: “Tanks are forbidden to turn here.”

Things got much more complicated as the mobilization militarized. Many radical circles were confused and could not take a position; one must understand that France is a very Islamophobic country. Many people could not accept the fact that you can be religious, Muslim, a combatant, and a revolutionary without wanting to impose Islamic law in Syria and without necessarily being any more misogynistic than some male comrades in the West.

In general, even in activist communities, people were ignorant about the existence of self-organized structures and practices within the Syrian revolution. Everyone talked about Rojava without understanding that there were local councils, hospitals, schools, coordination committees, and media centers self-organized in most of the neighborhoods, towns, villages, and cities in the areas liberated from the regime, independent from the influence of the PKK. In the discussions following our presentations, many people were like, “Why didn’t you speak about Rojava?”

In one way, they were right. Our silence in relation to Rojava was not completely justified. From our point of view, the obsession with Rojava common in radical circles in the West pushed us into a strange position, compelling us to say “Hey, we exist too!” We were in danger of reproducing the same errors in our own analysis, behaving as though Rojava and the Syrian Revolution were two entirely separate realities. We realized this and tried to develop a discourse that would enable us to speak about the Syrian revolution without centering the discussion on Rojava, but at the same time without ignoring its existence.

Most people would say the events of the Syrian revolution are too complicated. To give these people the benefit of the doubt, let’s say that yes, the armed conflict that is still taking place in Syria is not an easy subject to master. However, this is no excuse to claim that there is no popular uprising in Syria involving ordinary (very brave) people.

I think that this is what happened in radical circles: on the Kurdish side in Rojava, things seemed clear. Most people I talked to had the same discourse: Rojava was a revolution in a Middle East filled with Islamists and dictators. The points of reference were very clear: anti-fascism, feminism, ecology, and direct democracy. Ironically, I think this is the reason why some people who supported Rojava knew so little about what was happening on the ground or about the ideological underpinnings and history of the PKK.

Certain French radical circles, especially the autonomous ones (with a few exceptions), were relatively closed in on themselves. A culture of secrecy and opacity was performed dogmatically in many situations, which made it easy to feel excluded from many militant spaces; sometimes this was a habit rather than an intentional tactic, which is especially unfortunate. Additionally, we could instantly feel that there was a certain expected language and other codified forms of conduct that were incomprehensible to newcomers. At the beginning, I thought that the problem was that my French was poor; later, I discovered that even politicized and engaged French people often feel excluded as well in autonomous circles. It wasn’t easy to find a point of entry. As much as I understand the necessity of non-public activities—since we have spent our whole lives in Syria under surveillance—it is a shame to lack public points of entry that could be welcoming to activists from other countries.

In most radical circles, it was seen as praiseworthy to include non-French and especially non-European activists in French collectives and actions—it was considered a good sign of diversity. At the same time, there was very little space for non-European activists to contribute to transforming French militant discourse and practice. I think the principle of equality is to listen to what activists from other countries have to say, not only in terms of stories and testimonies, but also in terms of analysis, strategic reflection, and tactical experience.

R—: I arrived in France five years after the revolution began. The French were divided in terms of knowledge and involvement when it came to supporting the Syrian movement. On the one hand, there are those who have in mind the image of a war and of an international conflict with thousands of migrants landing in their country. For this part of the population, the portrayal of Syrians as victims has managed to direct their support to the humanitarian sectors. This contributed to them putting aside the political aspect of the revolutionary movement, seeing the Syrians who arrived in France as passive victims who needed help, unfit to be actors in political life.

On the other hand, when I arrived in France, I met a group of anarchist friends who are loyal to the revolution. They are politically involved in the French support movement and have a more bottom-up perspective. They don’t rely on the mainstream media for information, but listen to Syrians—reading and listening to their testimonies, contacting them and getting involved with their struggles.

Delicious food, courtesy of the Syrian Cantina.

What were the most useful things that people in France did to extend solidarity to you?

L—: There are many initiatives and associations in France that are still welcoming refugees and helping them with housing, language classes, administrative processes, gaining access to university education, and so on. This was decisive and really helpful, especially in the first period after I arrived in France.

Some initiatives were also organized to send humanitarian aid and resources to projects inside the liberated or besieged territories, especially self-run schools and hospitals.

Another thing that was useful was the possibility to use spaces in social centers to host events and talks about the Syrian Revolution. We would like to thank the Parole Errante in Montreuil, which opened its doors to Syrians. Having a space to organize is crucial. We would also like to warmly thank the Maison Ouverte in Montreuil, which hosted our project in its initial phase.

Other types of useful support are related to media and information. Websites like Lundi.am did a great job covering the Syrian revolution; the journal CQFD dedicated a whole issue to the Syrian revolution and regularly published articles and reports from the point of view of the civil mobilizations and progressive forces on the ground. We can also mention different translation initiatives, which worked to make literature on the Syrian Revolution accessible in French.

Finally, it was helpful that some groups hosted talks, reading groups, and events at which Syrian revolutionaries were invited to share their experiences. Those were crucial moments not only for informing people about the Syrian Revolution but also to give us the chance to meet people, creating a network of allies and establishing personal relations between activists.

One of the things that was not very helpful was speaking about the Syrian “conflict” or “war” on our behalf, exclusively from a geopolitical or humanitarian standpoint. Both standpoints contributed to rendering invisible a popular struggle that was facing the regime not only on a military basis but also on the level of civil society. Both standpoints depoliticize the resistance and minimize the political agency of the actors on the ground. The humanitarian approach focuses on the figure of the victim, whether it is the Syrian who experiences the war or the refugee who manages to escape it—in both cases, as a helpless individual who invites sympathy (but ultimately apathy). The geopolitical approach is less empathetic: war victims and refugees are numbers in a game of Risk in which all analysis is state-centered, forgetting that it is people’s efforts to live with dignity that matter most.

On western forms of solidarity, we recommend “A Critique of Solidarity.”

Preparing dinner the Syrian Cantina at the AERI space.

How have Syrians’ experiences in the diaspora differed according to class, ethnicity, social connections, and other factors?

L—: From early on, the regime tried to use the divide and conquer method in order to combat the popular uprising. The regime’s propaganda used the ethnic and religious diversity of Syrian society to pit communities against each other and instrumentalize tensions. When people today call what happened in Syria a “civil war,” they need to take into account how it was in the regime’s interest—indeed, it was a conscious strategy—to frame the situation in those terms in order to be able to present itself as the “secular” entity, the sole power that could guarantee peace for ethnic or religious minorities. In fact, the majority of us in the Syrian Cantina come from religious minorities. The regime has never protected our interests, and if it did so at any particular moment, it was purely out of political calculation, not out of a belief in the modernist principle of separation between state and religion.

After eleven years of armed conflict, it would be naïve to say that tensions do not exist between ethnic or religious communities. However, we insist that in the first years of the revolution, support for the regime and opposition to it were not distributed according to ethnic or religious lines. Even today, in any ethnic or religious community, you will find people who support the regime and others who oppose it, including among Alawites (the branch of Shiism that comprises Assad’s religious minority).

However, the war was definitely much harder on the lower classes. The consequences of inflation rendered basic necessities barely affordable to a large part of the population. For those who don’t have family members outside the country who can afford to send money in a foreign currency, daily survival is absolutely critical.

As is always the case with wars, certain classes get richer by means of monopolies or by creating new markets and profit models based on the scarcity of certain items. Additionally, Assad’s Syria, especially under Bashar, has been a system of crony capitalism in which corruption is encouraged as long as the regime gets its share of profits and maintains political control. This has intensified over the past decade; the most recent example is the growing drug industry, as Syria has become one of the chief producers and exporters of the drug captagon, which has contributed to stabilizing the national economy a bit.

Many of the people who were not able to get to Europe or other western countries could not secure a visa for lack of money or social connections, or could not gather enough money to find a non-legal means of escape, whether by obtaining fake travel documents or by crossing borders illegally. Illegal migration is expensive!

So the two chief factors determining whether people could get to European countries are definitely class and social connections; this also explains why most Syrian refugees are still in neighboring countries. But let’s not forget, some people also decided to stay in Syria, whether because they refused to leave the struggle or because they refused to leave their homes, perhaps out of fear of experiencing the uprooted life of a refugee.

The experience of being a refugee differs significantly according to whether you live in Lebanon or Turkey or in France or Germany. The common thread, without a doubt, is a sort of ambient racism. One thing needs to be said in relation to Europe, and France in particular: Islamophobia is one of the chief causes of discrimination, especially for women. If you happen to be a practicing Muslim, and if that is somehow visible in the public sphere, you will have a harder time as a refugee. In France, this is even true for French citizens.

To be clear: Islamists stole the revolution in Syria and did a tremendous amount of harm to the communal and social fabric. They are our enemies as much as Assad! However, that should not leave any space for Islamophobia, whether among Europeans or “secular Syrians.”

Those who are inside Syria deserve material support, especially those who are internally displaced in refugee camps in atrocious conditions, spending several winters in tents under the snow with little hope of change. There are several initiatives that you could support, such as this one.

Beyond material support, there is recognition and moral support: it is important to remember that any future change in Syria will be first and foremost carried out by those who are still there, even if the diaspora will have an important role to play. We need to pay attention to what the people there have to say, to the mobilizations and initiatives they are capable of organizing even in regime-controlled territories.

You can check this Facebook page for memes and anti-regime slogans posted anonymously from within Syrian territories controlled by the regime today.

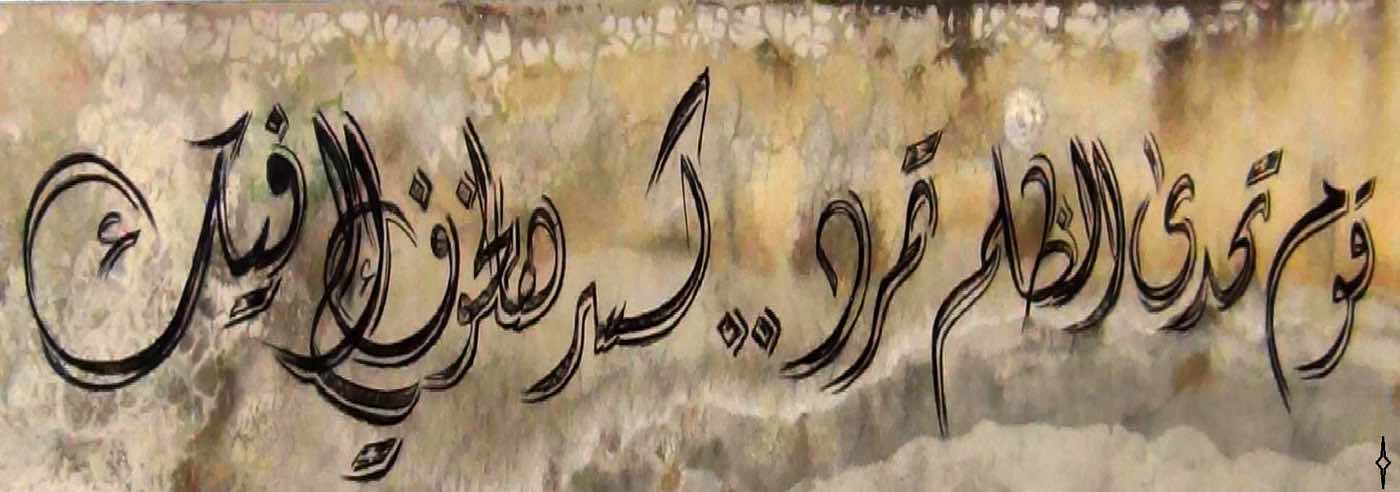

Graffiti in Syria in July 2012: “Revolt and defy oppression.”

What would have been necessary to make the Syrian Revolution turn out differently?

L—: I don’t know if we can provide an analysis of how the revolution could have “won”: we are aware that the fall of Assad would not have automatically brought freedom and dignity to Syria. We are also aware, as some of us learned from living in European countries, that free elections and “democratic transitions” do not guarantee a functioning democracy in which people are able to determine for themselves how they live. The examples in Tunisia and, more recently, Sudan show us that toppling the regime is just the first step in a much longer struggle towards self-determination and justice.

However, we can describe some elements that could have reduced the immense losses we suffered and perhaps might have changed the balance of power in favor of the forces working towards emancipation.

-

A no-fly zone before the Russian intervention in 2015. A no-fly zone would have changed the balance of power in favor of the rebels who, in the first years of the revolution, had the capacity, on multiple occasions, to achieve a military victory against regime forces. A no-fly zone was requested by civilians on the ground, not only by armed groups. Today, we see the same demand in Ukraine: “Close the sky and we do the rest.” We cherish our autonomy and hence refuse external intervention. However, we know that if we had not received barrel bombs non-stop on our heads (targeting hospitals and schools as well as military positions, just as is happening in Ukraine today), more of us could have survived and resisted. We could have dedicated more time to imagining and implementing political alternatives to both the regime and the Islamists, instead of digging our loved ones out of the rubble of our destroyed homes.

We see the same thing today—a situation in which American and other western activists refuse the idea of a military intervention, putting forward anti-imperialist arguments. One of the arguments is that a military intervention is not in the interest of the local population. The paradox is blatant: as the local population asks for military intervention, western activists whose lives are not threatened comfortably write anti-war texts explaining how we should put first and foremost the interests of the local population that they are not ready to listen to. Paternalism.

-

More decisive military support: access to more defensive weapons more quickly. In Syria, there was a huge problem regarding timing. When military support reached the rebels, it was always too late and insufficient, as if to render it impossible for the regime to fall. It is difficult to write this text today without making references to the Ukrainian case. But let’s refrain from comparisons for the moment and focus on Syria.

There was a lot of hesitation to support Syrian rebels, especially after military intervention in Libya turned out so badly. The hesitation and indecision of various western countries during the first years of the Syrian Revolution, when it came to providing the rebels with defensive weapons that could counteract aerial attacks and missiles, paved the way for other actors to intervene, imposing their external vision of what the armed (as well as civilian) opposition should look like. The hesitation of the West—which avoided threatening the regime, intervening with “intelligence and training,” but always too late—contributed to prolonging the armed conflict for years, giving Islamist forces the opportunity to take control of territories. The transnational support for Islamist armed groups outpaced material aid to the Free Syrian Army and other brigades that were neutral on religious matters.

In one sense, we can’t say that western countries carried out no real military intervention in Syria. The international coalition did intervene to bombard ISIS positions—and to do that, they ignored all treaties and legal frameworks. Western countries intervened in Syria to support the Kurds and combat ISIS, but never to attack the roots of the bloodbath, Assad’s power. It was Assad that was responsible for more than 90,000 of the 159,774 civilian deaths over the past eleven years, according to both the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) and the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR).

This selective approach, in which western governments refused to act against Assad while acting elsewhere in Syria, represents an intentional intervention in the Syrian conflict.

As for Barack Obama’s famous “red line,” Syrian revolutionaries and opponents of the Assad regime view Obama as having handed over the “Syrian file” to Putin, hoping that Russia would take over the role of the United States as the world’s police. In 2013, around two thirds of the territories in Syria had been liberated and self-governed. In 2015, the Russian army began coordinating the military operations of the Syrian regime. In 2016, when Aleppo fell, it marked a point of no return in terms of the balance of power. A military defeat became almost certain for forces opposed to the regime, thanks to Russia but also to Iran and Hezbollah.

To be sure, we lived with refugees from the disastrous war that the US inflicted on Iraq, and we know what US imperialism means in our countries. Yet, in this particular case, unfortunately, the withdrawal of the US and other European countries from the war of influence in Syria meant years of continuing massacres and, ultimately, the stabilization and consolidation of Assad rule. Eleven years later, Assad is still in power, despite being among the 21st century’s most renowned butchers.

-

We should have been more alarmed, sooner, about the expansion of Islamist groups. In some territories, people took too long to recognize the threat that Islamist groups represented to civil mobilization and the spirit of the revolution. In the protests in the early years of the revolution, we called for unity between ethnicities and religions against tyranny. The growing presence of Islamist groups radicalized the whole terrain, so if you wanted to get financial support or weapons from neighboring countries you had to modify your discourse—shifting it to a religious tone, changing the name of your brigade or association, and putting “God is greatest” on your banner. Rebels and revolutionaries considered the regime to be the chief enemy, so combating Islamist groups and discourse wasn’t always a priority.

This is somewhat understandable, since up to today, the regime remains the principal cause of deaths and displacement in Syria. We should never forget that the regime also played an active role in releasing Islamists from prisons during the revolution, and avoided direct attacks in their bases. Considering that Islamist groups were also fighting the regime, revolutionaries hoped that in the short run, Islamists would help bring Assad down and then it would be possible to deal with the Islamists’ presence. It is also important not to forget that there were many protests, up to today in Idlib for example, that opposed both the regime and the Islamist groups—who have not failed to be tyrannical wherever they have taken control of territory.

-

Support for and recognition of self-government initiatives such as the local councils would have been a crucial factor. It was practically impossible for nation-states to acknowledge non-state actors, and even more so to acknowledge those that were self-organized, decentralized, and without clear leadership (in contrast to the Kurdish case). Those local councils were the best entities that could represent the interests of the Syrian people, since they organized the politics of daily life and took over managing services. Their members were democratically elected or appointed by locals, in a model similar to the Zapatista council of good governance.

It is not surprising that states did not want to recognize these entities—though comrades should have! Instead, governments symbolically recognized the Syrian National Coalition or Council, a sort of top-down structure trying to find diplomatic solutions; they just met with United Nations representatives from different countries and held a series of talks that had practically no effect on the ground. For a period of time, the Syrian National Coalition had some support from revolutionaries, but hope that change would come through these mechanisms rapidly vanished and a large part of the revolutionaries became critical of these coalitions, which were disconnected from reality.

-

More alliances with components of the Kurdish revolutionary movement. Whether it was the Syrian National Coalition or other political entities plagued by nationalism and racism, the refusal of a plurinational Syrian horizon and the idea of federalization was a missed opportunity for revolutionaries in Syria of all backgrounds, Kurdish and otherwise. Instead of the Kurdish revolutionary movement having to be neutral or cooperate with the Assad regime, we could have imagined the Syrian revolutionary forces and the Kurdish revolutionary forces joining together on the basis of common interests in order to overthrow the regime. There were many reasons, on both sides, why this did not happen. But for the future of Syria, a reconciliation between these two revolutionary forces will be necessary in order to overthrow all types of tyranny, including the regime and the Islamists, and to ensure that no new repressive power structure can emerge, not even from the PKK or PYD.

-

Finally, the revolution would have turned out differently if leftists had not repeated Assad’s propaganda to the effect that there was no alternative: you had to either stand with Assad or you stand with the Islamists. There was an alternative! All of this is difficult to explain now, but discourse is always a major part of the battlefield, and the people’s struggle and resistance were just not audible. The consequences of this were huge: the distortion and falsification of the historical record.

Today, if you go to Wikipedia (in English, for example), you can’t even find an entry for the “Syrian Revolution.” You can only find the Syrian “civil war.” It is so violent to find that this historic event that changed the lives of millions of people, if not politics worldwide, has become completely invisible. This language is reductionist and inaccurate. In fact, if we want to be precise and nonpartisan, the least we can do is to acknowledge that it was not a civil war but a transnational conflict, since practically all the western governments and powerful regional or international states intervened in Syria in one way or another.

Preparing the dinner for the Syrian Cantina at the AERI space.

How do you continue organizing to support people in Syria and people in the Syrian diaspora today?

L—: We try to provide financial support to initiatives in Syria and the surrounding region. Most of these initiatives are “humanitarian” and aim to address the harsh living conditions, especially in refugee camps. We have organized campaigns in the Parisian region to collect first aid necessities, clothes and medicine, and other resources to alleviate material hardships in periods of intense conflict in the territories under siege.

We organize an annual event to celebrate the anniversary of the Syrian Revolution: it is very important for us to invite speakers who are still organizing and active inside Syria. It is also an occasion to renew the heritage of the Syrian revolution and speak about the aspects of it that few people here know about, such as the experience of local councils. This year, we will hold a talk on the axis of counterrevolution, in which we try to deconstruct pseudo-anti-imperialist arguments that support Hezbollah or celebrate leaders like al-Sulemany without acknowledging that those powers were not only counterrevolutionary in Syria but also, more importantly, in Lebanon or Iran as well.

With regards to the Syrian diaspora, we try to make the cantina a home that is open and accessible to everyone (well, except for regime’s apologists) and a meeting place to discuss politics, organize, and meet with other political communities in France. We believe that having a physical space for Syrians to meet is crucial in exile: most of us have relatives, friends, and families scattered around the world, our lives are fragmented, and there is a constant feeling of estrangement in relation to the world and other people, given our collective and individual traumas. The Syrian Canteen is a space to find respite and refuge.

It is also important for us that this space is open and welcoming and accessible to refugees from other countries. We don’t want to organize exclusively among Syrians. Our community, just like our existence, has become transnational and we have to embrace that instead of engaging in a process of self-ghettoization.

Finally, we try as much as possible to share news about mobilizations that take place in Syria as a reminder that people still live and organize there, despite the long years of war and violence.

You mentioned your complex relationship to the experiment in Rojava. Many people have heard about it over the past decade, but people do not always understand it in the context of the Syrian revolution as a whole. Can you describe how you see these events?

O—: I can try to answer from a French point of view,1 because since 2015 I have tried to reflect on the enthusiasm of radical and libertarian Western leftists for Rojava, and on the differences between the Syrian revolution and the Kurdish revolution (see this article in French). As a supporter of the Kurdish cause in Turkey, I started out very attracted to the experiments in Rojava before being quite confused by discussions with Syrian revolutionaries in exile who had a completely different point of view on the subject.

In my opinion, the question is not whether to support Rojava and the Kurdish revolutionary movement. Rather, the problem emerges when this is done in a fantasized way, and even worse when this support is coupled with a total ignorance of the context in which it has taken root and its relationship with the Syrian revolution that started in 2011. To try to understand all this in order to be able to take a position, we must return to the differences and disagreements between these two revolutions of different types.

A mural in Syria in May 2014.

Before presenting them in detail, there is something fundamental that must be remembered: the Kurds who were oppressed as an ethnic minority for decades by the Syrian regime are not interchangeable with the Kurdish revolutionary movement embodied by the PKK in Turkey and the PYD in Syria, two sister parties that set up the Rojava project starting in 2012. It is important to make this distinction, because while many Kurds have participated in the Syrian revolution and contributed their experiences of political struggle, the PYD and PKK have remained neutral or even opposed to the Syrian revolution. We could say that they took advantage of the destabilization created by the uprising of 2011 to fulfill their project of establishing an autonomous Kurdish territory organized according to the ideological principles of their party, democratic confederalism. Nearly 40,000 fighters and cadres of the PKK, formed in the mountains of Quandil in Iraq and Turkey, arrived in the Kurdish majority territories of northeast Syria in 2012.

The most important reason for the antagonism is the PYD’s relationship with the murderous Bashar regime: while the details of the negotiations are still unclear, it seems that in early 2012, the PYD-PKK negotiated with the regime to return to Syria and take over the three areas of Kurdish settlement on the border with Turkey—Afrin, Kobane, and Jazira—in exchange for neutralizing Kurdish demonstrators who were with the revolution and promising not to make a common front with the Free Syrian Army. Arriving a few months after the outbreak of the revolt, the PYD-PKK cadres went so far as to repress demonstrations expressing opposition to the Syrian regime.

Once the PKK-PYD was installed in northeastern Syria, a game of alliances definitively buried the possibility of a junction between Syrian and Kurdish revolutionaries. The two sides, both heavily dependent on foreign aid to guarantee their survival, have come to form opposing associations. The PKK tried to secure Russian protection when Russia was already bombing Syrian rebels. At the same time, several Free Syrian Army militias were financed, armed, and supported by the Turkish regime of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the PKK’s sworn enemy, who was working to isolate those he considered to be one of Turkey’s main threats, just as Bashar al-Assad did with the rebels. Today, many former Syrian revolutionaries, now paid by Turkey, are used by the Turkish regime to attack Kurdish territories and commit horrible atrocities. Considering that in 2013, the Syrian regime was close to falling, we can say that the help of organized and militarily trained fighters would surely have brought the coup de grace to Bashar.

The explanation of many Kurds is that they thought that in the end, even if the Syrian regime fell, they would be betrayed by the Syrian opposition—they would not be able to implement their communalist project and Kurdish people would not be granted autonomy or rights. This shows that the mistakes were not only on one side. The Syrian opposition based in Istanbul—which is itself criticized by revolutionaries inside Syria—was negotiating about the future of Syria, thinking that victory was near, while refusing to include the PYD-PKK in the discussions and refusing to grant protected status to the Kurds. Nationalist elements of the Syrian opposition did not want to recognize languages other than Arabic as national languages and viewed the idea of confederalism as a means to divide Syria.

“The revolution is here with the people, not in Antakya” [i.e., in Syria, not in Turkey, where self-styled representatives of the Syrian revolution were holding court].

These tensions derive from two different visions of the revolution and the future. The PYD-PKK pursues a confederalist and pluralistic vision of Syria and the region as a whole, with a recognition of minorities and autonomy for Kurdish people. By contrast, many Syrian revolutionaries pictured the Syria of tomorrow as an indivisible republic, inspired by a republican vision in the style of the French revolution.

Today, the situation is even worse: the compromise with Bashar has intensified since 2018, because the PYD, in order to protect itself from the Turkish invasion and from being abandoned by the Russians and the USA, has asked for the help of Bashar and made many concessions to the regime in return for protection facing the invasions of Erdoğan. Consequently, for example, several agents of the regime have returned to the Kurdish territories of Rojava. In Afrin, we even see the Syrian army parading with regime flags and portraits of Bashar. In 2021, the PYD-PKK went so far as to suppress riots and kill demonstrators who were protesting against compulsory conscription in Manbij, a city they administer. For many Syrian revolutionaries, this is unforgivable.

To conclude, I think it is important to understand that we are talking about two different revolutionary movements. On the one hand, the Syrian uprising, an unprepared popular revolution that made possible the massive politicization of a population that, until then, had little access to any form of social and political organization, but which ultimately resulted in the military hegemony of armed Islamist groups, as well as the victory of the Bashar Al-Assad regime and his allies. On the other hand, the Rojava Revolution is a case of a revolutionary struggle orchestrated by a party, the PKK, with nearly 40 years of experience. The PKK has succeeded in stimulating the popular political imagination on an international scale via its innovative experiments and its critique of the nation-state. Nevertheless, it has difficulty convincing people that Kurdishness is not at the heart of its project, and it still draws its strength from the often authoritarian and pragmatic strategies of Leninism and the liberation struggles of the 20th century. Caught between a belligerent Turkey and a Syrian regime that seeks its surrender, its future remains uncertain.

For our part, in the Syrian cantina, we seek to make dialogue between the activists of both experiences, as long as our interlocutors do not deny the existence of a real popular revolution in Syria and respect the sacrifices of the Syrian people in their struggle against oppression. From that starting point, we can hear a critical opinion and debate regarding the attitude of the Syrian revolution towards the Kurds.

What perspective have your experiences given you on the importance of internationalism?

L—: After the Syrian revolution and war, we have the feeling that as Syrians we understand the world better and are more capable of debunking myths such as “the international community” or the impact of the “United Nations” and so on. We do not reject these entities on merely ideological grounds, but on the basis of our experience, as a result of what we saw happening month after month, as the world gradually turned a blind eye towards what was happening in Syria.

We quickly learned that we cannot depend on those types of institutions. Also, although we would like to live in a world in which borders do not divide us, we are aware that for the moment, we have to think of “intermediary” propositions and solutions, via which we can collaborate and mutually support our struggles within the existing divisions imposed by states.

We understand from our experience of the Syrian revolution that the conflict we face is transnational, so our analysis and our propositions to change the situation must not be restricted to a national framework. We wish that the Russians would have done more to oppose Putin’s military intervention in Syria, that more Lebanese people would have refused to send their children to fight with the banner of Hezbollah on the side of the regime in Syria, that direct action would have broken out throughout European capitals when Aleppo fell.

What is very clear today is that the people want to overthrow the system. In 2019, from Hong Kong to Iran, popular uprisings exploded everywhere in the world with more or less similar demands and methods. We need to take a step further, to go beyond similarities towards coordinated actions and the construction of transnational forces.

We live in a globalized world in which we all suffer from the same international capitalist system, just like the ecological crisis, just like reactionary nationalists politics, just like patriarchy. We don’t suffer in the same way, depending on our skin color, gender, sexual orientation, and class—but if we decide to combat capitalism to try to create a world free of all kinds of domination and exploitation, there is no alternative but to work together. It is a vital necessity, not a utopian luxury.

The internationalism we aspire to is combative. It is not some naïve and depoliticized version of “we are all united in our humanity.” It is an internationalism from below, rooted in local self-organizations and social movements.

We can also explain our internationalist perspectives from our experience of exile: not being a citizen of a country, being “illegal” in a place, puts you on the same side as many other people with whom you had no previous relation. For example, when you fight alongside Ethiopian comrades in France on matters related to asylum, your perspective is no longer the same. You can’t go back to seeing the world from the point of view of your home country or that of your “host country”—you have something else, a vantage point from which you can deconstruct toxic nationalism.

O—: Personally, I really tried to understand why the Syrian revolution had received so little support in France. There are several factors involved: the complexity of the conflict, the lack of preexisting links with Syrian activists, a latent racism, the lack of common reference points, the propaganda of the Syrian regime and its surrogates in France, and so on.

Also, in France, internationalism is very weak. Even in anarchist or autonomous circles, there is a lack of interest in international revolts (with the exception of Rojava, the Zapatistas, and Palestine). It’s not a coincidence that there are no articles in the French press about our festival, “The People Want,” or, more generally, about the Syrian Cantina, whereas there are already articles in Arabic or English for instance.

Unfortunately, those who are most vocal in expressing an internationalist and anti-imperialist position often have bad positions—for example, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, who supported Putin in Syria, or groups that support counterrevolutionary and murderous regimes or groups like Hezbollah or the Iranian regime.

For me, the Syrian revolution has been an incredible source of inspiration. What you learn there is proof that internationalism is rich in lessons for you at home too. I believe that any revolutionary who thinks about how to make a revolution in the 21st century must make an effort to try to understand the mistakes and successes of the uprisings of the last ten years as well as those to come.

After experiencing the lack of support from the radical left in France, I told myself that it should never happen again, that we could no longer afford to give so little support to uprisings like this. That’s why we are trying to be responsive to the situation in Ukraine, to think about how not to leave the comrades there isolated, to make their voices and their positions heard. We believe that the Syrian lessons, especially in terms of international reaction, have a lot to tell us about what will happen in Ukraine and what we can do from the outside. This is why we wrote an article about it.

Graffiti in Syria in July 2014.

How can we combat false notions of “anti-imperialism” that serve to legitimize rulers like Assad? Where do these come from and what is at the root of them?

O—: In France, a certain radical left often defends the policies of Putin, the Iranian regime, the Lebanese party Hezbollah, and therefore, implicitly, the Syrian regime, even if it is harder to do so overtly.

In addition to fighting them, I believe that it is important to understand the roots of these positions because we encounter them in regards to several different conflicts around the world—and we might encounter them even more in the years to come, especially after Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

According to us, this kind of “anti-imperialism” has two different origins. First, it derives from a vision inherited from the “campism” of the Cold War. During the Cold War—the years of “third worldism”—there was an ideological focus on supporting actors close to socialism (the Soviets, Cuba, the Algerian FLN, the Palestinian PLO, and the like) against the expansionist interests of the “capitalist” bloc of the West led by the United States. The problem is that thirty years after the end of the Cold War, many entities of the radical left remain stuck in this vision inherited from another century.

In a context in which these groups are no longer connected to states or organizations that are ideologically close to them, this doctrine transformed into the idea that one should support any opponent of American and Western imperialism—all the more so if one is French or American, for example. The adherents of this approach hold to it even when the adversary is itself bellicose, totalitarian, or tyrannical and massacres its own people—as the Chinese, Iranian, Syrian, and Russian regimes do.

Today, this vision answers in a simplistic and opportunistic way to the expression “the enemies of my enemies are my friends.” It totally neglects the possibility that one can espouse an anti-imperialist position (as we do) rejecting Western expansionism (as in Libya, Mali, or Iraq, for example) while also rejecting the expansionism of regimes like Russia or Iran. For example, as Iraqi revolutionaries did during the 2019 revolt, chanting “neither USA nor Iran.”

The other origin point of this false “anti-imperialism” is the way that the Palestinian cause has been associated with the self-proclaimed “axis of resistance” to Israel, supposedly embodied by the Iranian regime, Syria, and the Lebanese Hezbollah. As a consequence, in France, several militants—many of whom are from poor neighborhoods—do a great job in local organizing but defend totally reactionary positions on an international scale. This includes supporting Bashar Al-Assad, Hezbollah, or the Iranian regime under the pretext that they are the only credible opponents of the main enemy, Israel.

All this can be explained by the progressive decline of pan-Arab, socialist, or leftist movements over the last thirty years. These have been replaced by something that is portrayed as “popular resistance” but in fact is a coalition of authoritarians, embodied by the Iranian regime, Assad’s regime, and the Lebanese party Hezbollah as the central figures in the defense of the Palestinian cause.

Three events played a crucial role in the evolution of this situation.

-

The Iranian revolution in 1979 with the arrival in power of the mullahs (to the detriment, within the revolution, of the Marxist revolutionaries). They quickly positioned themselves as the great enemies of Zionism in a context in which few Arab republics really maintained their opposition to Israel. Up to today, they are a source of massive financial support to the Palestinian party Hamas.

-

The war in Lebanon between 1975 and 1990, during which the Palestinian and Lebanese left were defeated. The main winners were the Shiite parties and Hezbollah in particular (financed and armed since 1982 by the Iranian regime), because it is the only actor authorized to keep weapons in the name of its role in the “resistance” to Israel.

-

Finally, the Israeli offensive in Lebanon in 2006. During this conflict, Hezbollah managed to stand up to the Israeli army, which gave it a special aura both in Lebanon and all around the region. A Lebanese anarchist once told me that at that moment, a large number of left-wing activists and Lebanese communists who had been involved in the Palestinian cause for years rallied to Hezbollah. He had himself tried to go to the border to join up, but was refused because he was Sunni, not Shiite.

This touches on a more complicated point: there are currently no actors defending our positions that are capable of standing up to Israel. This is why a similar shift has taken place in France and many activists who used to defend the Palestinian cause from the left have ended up supporting reactionary groups. In 2006, at the time of the Israeli bombings, there were large demonstrations in Paris and even riots. The Palestinian cause is arguably the issue that mobilizes the most people in the poorer districts. It is important to understand that for this generation, those events symbolized an important moment of dignity in a country as racist as France, where Muslims are constantly stigmatized and oppressed. This is why many people who became politicized in these demonstrations still see groups like Hezbollah as heroes of the Palestinian cause and even of anti-imperialism.

Unfortunately, Sulemani and Hassan Nasrallah are nothing like Che Guevara or Ben Barka. The latter did not defend a reactionary and authoritarian ideology and did not crush revolts in their own countries as Sulemani did for the Iranian regime in Syria, Iraq, or at home in Iran.

Finally, it is important to remember that the Hezbollah of 2006 is not the Hezbollah of today. Over the past sixteen years, it has sent thousands of young Lebanese to be killed in Syria in order to try to crush a democratic revolution; it has assassinated opponents of its policies; it has suppressed the uprising in Lebanon in 2019 and seems to have had a real role in the explosion in the port of Beirut in August 2020. In Lebanon itself, Hezbollah no longer has the same reputation. It has seen defections by the hundreds. Those who support the Syrian regime and Hezbollah among the Lebanese left (much less numerous) are increasingly excluded from popular gatherings.

Maintaining a fixed idea of the political regimes in the Middle East is an orientalist approach that denies the transformations that led to our present situation. It is as if we were still supporting the Algerian regime today in the face of the Hirak [the Algerian protests of 2019–2021] on the pretext that the generals are the heirs of the Algerian revolution that drove out French colonial rule. Since those days, this regime has monopolized all power, silenced its people, unleashed a civil war, and repressed dozens of revolts. In fact, nobody thinks of supporting it.

For all these reasons, it is urgent to update our conceptions of internationalism and anti-imperialism. These regimes and parties do not embody the emancipation of the peoples of the global South or the “non-aligned.” They are authoritarian and counterrevolutionary forces that suffocate their peoples.

Supposed “anti-imperialists” never say anything regarding these questions. They do not say a word about the political violence of which the Syrians, the Iranians, the Russians themselves are victims. Worse, they spread disinformation and propaganda directly from these authoritarian regimes. In depriving the inhabitants of these countries of any political role, even those who espouse ideologically similar positions, false “anti-imperialists” embody the very essence of imperialist and racist privilege.

The advice we would like to give to people who espouse these politics is to come back to listening carefully to the grassroots, to the voice of the inhabitants of these countries, in particular those who share ideas close to ours—egalitarianism, feminism, direct democracy, self-determination. Instead of talking about the people or the working class, go and meet them when they rise up—not only in the West, but also in Syria, Ukraine, or Iran. Especially since many exiles from these countries arrive in western countries.

In some ways, it is more comfortable for some people to support these regimes because it enables them to have strong figures to defend—it makes things very simple. But we can’t support these groups. Supporting them would mean cutting ourselves off from comrades in exile here and from potential comrades who are fighting for their lives, freedom, and dignity there.

That’s why the Syrian Cantina and the Peuples Veulent team has made the fight against this kind of “anti-imperialism” one of its main objectives. In our view, the most valuable points of view on the issue are often those that come directly from the Middle East—because, having long been caught between the devil (America) and the deep blue sea (the authoritarian regimes of the region), they have developed discourses that are grounded in the immediate situation there.

We have to acknowledge that the world is no longer the same as it was, that we are orphans of emancipatory ideologies competing with capitalism. But one thing is certain: we will not succeed in building credible alternatives by throwing ourselves into the arms of authoritarian regimes.

More delicious food, courtesy of the Syrian Cantina.

Advice for Refugees Organizing in a New Context

What can you say to others who may become refugees about how they can continue their organizing efforts in a foreign context? And to locals who want to support refugees in doing this?

L—: To refugees we say—if for some reason, some governments are somewhat favorable or less repressive to people from your country and situation, do not ever feel that you owe them anything in return. It is always people, locals, associations, and organizations that do most of the hard work to welcome exiled persons. States are never totally on our side.

Try to inform yourself as much as possible about the different struggles and the different political communities that are active in your place of exile. In order to build links with local activists, it is important to understand what their fights are: talk to them, ask them questions, ask them to provide you with the militant literature they read, for example; identify common grounds that you can share and fight for.

Don’t expect people to come and support your cause at home just because you are a refugee or because you have escaped war or a natural disaster. If you intend to maintain consistent and durable links with local activists and to continue organizing from exile in relation to issues at home, it is important to go beyond immediate responses and relief actions, to build confidence and friendships. Sometimes, the best way to share your struggle with locals is to organize concerts and film projections, to dance and eat together. We need joy, humor, and festivity in our struggles, especially when we carry heavy traumas within us.

Remember that there are people from other nationalities in the place that you are exiled, whether they are refugees or not, who may share a situation similar to yours. Making contact with them and establishing alliances and coordination with their communities can be empowering and eye-opening.

To locals, we say—organizing with refugees should not be restricted to humanitarian actions or solidarity work. It is a huge opportunity to learn about different tactics, political practices, and strategies that you could adapt to your local context; it is an occasion to find inspiration and compare reflections and analyses. Listen to what they have to say: not only the stories and testimonies of what they have suffered—although those are very important—but also their ideas regarding what change could like in their countries or yours.

Advice for Supporting Refugee Organizers

What can people around the world do to provide support for refugees in the Syrian diaspora and in other diasporas? What resources and projects do we need to create?

L—: There are many things that people can do to help out diasporic communities and refugees in their countries:

- Fight your country’s racist and xenophobic politics.

- Inform yourself about struggles in other countries and try to adopt internationalist standpoints in your local and national struggles.

- Give exiled persons the space to express and share their visions, ideas, and analysis. Listen to them. You might learn a thing or two.

- Treat exiled persons not only as people who are in need of assistance but as agents who can politically intervene beyond matters concerning their own countries of origin or their refugee status.

- Put your militant resources at their service as needed: printers, contacts, and more.

- Provide spaces and facilities that will allow exiled communities to self-organize. Your assistance and advice are vital, but don’t try to direct their self-organization.

- It is possible that you will have political divergences, that you will not agree on everything. This is normal; it is important to be able to confront and discuss these divergences. Don’t be afraid of difference: this is a chance for everyone to let go of dogmatism and a chance for the exiled persons to discover a new political culture and other ways of doing things. They might also learn a thing or two.

- Try as much as possible to offer translations into other languages in order to make discussions and activities more accessible to newcomers.

- Offer material, logistical, linguistic, and administrative support to individuals or collectives as much as possible.

We need more translations from Arabic to other languages and vice versa. What is so great about your work at CrimethInc. is that texts are immediately translated into multiple languages, giving access and connecting activists and realities from all around the world. It is precious, especially in relation to situations like what is happening in Ukraine today, to be able to get firsthand reports from comrades on the ground there in English, French, German, and other languages. At the Cantina, we are starting to think about how we can be more active in translating texts from and to Arabic. So this is an open call: if anyone would like to give some of their time to do so, don’t hesitate to contact us at cantine.syrienne@gmail.com.

That aside, we need a new International from below—whether that involves networks, regular meetings and encounters, organizations, platforms, or forums. We don’t know what form it could take, but we need to think more seriously about structures capable of concrete transnational solidarity, gathering strategic proposals and building a common alternative narrative in order to have an impact on the terrible nationalist and reactionary course of the world. What is happening in Ukraine makes this all the more urgent.

Graffiti in Syria in 2022.

What are some sources via which readers can keep up with the situation in Syria and the Syrian diaspora? How can we support you and other related projects?

To keep up with news and mobilizations from Syria or to support mutual aid work:

We also try to build a beginning of internationalist media. On cantinesyrienne.fr, you can find our activities and some articles in French and Arabic about the Syrian revolution and other struggles around the world.

You can support the Syrian Cantina financially here.

-

O— is the one non-Syrian member of the Cantina who participated in this interview. ↩