Twenty years ago today, at the peak of a movement against capitalist globalization, hundreds of thousands of people gathered in Genoa, Italy to oppose the summit of the eight most powerful governments in the world—the G8. The demonstrations in Genoa represented the high-water mark of an era of global protest, in which both confrontational tactics and police repression reached their apex. In a new era of uprisings, we stand to learn a lot from studying previous cycles of resistance. The following narrative history recounts the mobilization in Genoa through a series of firsthand accounts from the front lines.

Today, when distance has made it possible for some to romanticize the authoritarian state socialist projects of yesteryear, it’s important to remember that the worldwide anti-capitalist movement of the turn of the century only got off the ground after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. Neoliberal globalization had been in progress since at least the 1970s, but previous forms of opposition had been subsumed by Cold War binary politics. With the emergence of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, who of necessity innovated a horizontal anti-state model for popular resistance,1 a new horizon appeared before social movements, offering a fertile soil for the anarchist and autonomist currents that had been gestating since the 1970s.

In this context, a worldwide network of squatters, occupation movements, countercultural scenes, and indigenous activists developed a strategy of convergence in which they would come together, concentrating force on a target. This strategy was most visible in the famous mobilizations against the World Trade Organization and similar transnational entities—but the root system of long-running social and cultural spaces was essential to the success of these mobilizations, creating opportunities for people to go through a shared political evolution, build ties, and innovate new tactics and discourses. Punks who had played in bands together intuitively understood how to form affinity groups; environmental activists who had coordinated campaigns in the woods knew how to facilitate meetings involving people from multiple continents.

For two years—starting in London and Seattle in 1999 and spreading from Australia to Québec City—demonstrators converged from around the world to confront global trade summits. Some sought to petition for reforms, decrying neoliberal policies and transnational trade agreements. Others used direct action to send the message that capitalism itself was the problem—and that together, grassroots movements could abolish it from below.

By the time the G8 met in Genoa in 2001, tensions were running high. Politicians of all parties were losing ground to the social movements in the war for narrative, while pacifists and reformists were losing ground within the movements to those who argued that it was necessary to confront the police and inflict consequences on the ruling class. A month before the summit, during protests at the European Union summit in Gothenburg, Swedish police fired live rounds at demonstrators for the first time since 1931, striking three people and nearly killing one.

Although corporate media outlets claimed that the intensification of conflict was alienating people from the movement, the much-anticipated mobilization in Genoa drew unprecedented numbers. Among these, thousands of anarchists converged on the city, determined to take the offensive. For their part, police indiscriminately assaulted crowds with tear gas and batons, carried out high-speed vehicular attacks, repeatedly fired live rounds, shot and killed one demonstrator, and concluded the weekend by carrying out brutal raids on the Indymedia center and a school that had been housing demonstrators.

The bloody clashes in Genoa both terrified and galvanized people. Perhaps, left to itself, the anti-capitalist movement of the turn of the century would have continued to radicalize and spread; or perhaps it would have fractured, as some participants escalated and others jumped ship. We’ll never know, because instead, the attacks of September 11, 2001 changed the subject, distracting everyone from capitalism and from their own capacities, and inaugurating the era of the anti-war movement, which was both more reactive and more reactionary. The state security apparatus developed its own model of convergence, concentrating tens of thousands of police to defend high-profile events—a strategy that has only been outflanked by countrywide uprisings.

Today, the riots in Genoa have been buried under several sedimentary layers of history. But their legacy remains with us, largely invisible, and we stand to gain a lot by revisiting the lessons of those days. For example, from Chile and Hong Kong to the United States, countless young people have essentially adopted the black bloc tactic that occasioned so much controversy in Genoa, provoking some of the same conflicts. If we adopt a broader historical perspective, we may be able to solve some of the problems we face today.

One of the things that obscured the events of the G8 summit in Genoa at the time was that many people—even including anarchists like David Graeber—found it impossible to believe that such a large number of people had intentionally gone on the offensive, attacking police and carrying out property destruction on a massive scale. Many activists preferred to think of themselves as victims rather than as combatants in a revolutionary struggle. Rumors spread that the actions of the black bloc in Genoa were the work of undercover police. This is why, for the sake of historical accuracy, we consider it so important to present testimony from the anarchists who engaged in confrontational tactics in Genoa in 2001.

As climate catastrophes and global inequality intensify, we can consider their decision to escalate vindicated. The tactics that they employed at the time were no more extreme than the ones that catalyzed the George Floyd uprising in the United States last year. The only remaining question is how to ensure that such movements cannot be isolated and vilified—but rather, that they spread.

Consult the appendix for an array of other references about the anti-capitalist mobilizations in Genoa and elsewhere.

We are accustomed to seeing events like the resistance to the Genoa G8 from the perspective of the police, through the haze of history. The following accounts offer us a perspective from the other side of the barricades.

Arriving in Genoa: July 2001

This passage is adapted from an account that appeared in the final issue of Inside Front. “The Tracks of our Tears” in the book On Fire—The Battle of Genoa and the Anti-Capitalist Movement offers another perspective from within the same affinity group.

We caught the train from the UK to the French town of Nice and slept in the street for the night. The following morning, we were on a train heading towards the Italian border, anticipating the border guards’ usual antagonism—but thankfully, after a brief delay, we arrived in Genoa. We were dressed to try to blend in as “backpackers” to avoid the eyes of the law. We found our way to the Genoa Social Forum convergence center (GSF).

As the bus drove through the city, I felt like Spartacus taking on the Roman Empire. Out the window, I saw workers erecting fences and police patrolling the streets in squads, helicopters, armored vehicles, and cars. All my nightmares of a police state were actualizing themselves in reality.

People at the GSF advised us to stay in a park about a two-kilometer walk along the promenade—a park that had been designated a campsite for the duration of the summit. We set up our tents, wandered around, acquired some food, talked, and rested.

That evening, there was a meeting to organize camp security. We discussed why we needed to be prepared—especially after the police in Gothenburg had stormed the places where people slept. We sorted out security shifts, iron bars collected to secure the gate, and decided upon an alarm in case of a raid—although there were small groups of people who maintained that the State could not possibly raid us!

Different branches of the Italian forces of repression together during the demonstrations, with tear gas and live ammunition at the ready.

We meet several English-speaking anarchists and begin to work out how to pursue our intentions in Genoa. We formed an affinity group of eight, all prepared to wear black.

Prior to the weekend of action, the most exciting part was meeting up and networking with people around the city. We took quaint backstreets to meet with other anarchists in order to avoid being harassed by police, comparing notes so we would all be aware of the various affinity groups’ intentions. The feeling of being connected on the basis of our shared desire was exhilarating.

Eventually, we had some idea of how Friday’s “Day of Action” would go. Some groups would attack symbols of capitalism, such as banks; some would deliberately attack the police in order to draw away and concentrate their forces; and others would attempt to pull down police fences and attack the “red zone,” the area behind the police lines where the world rulers would be meeting, as demonstrators had done during the Free Trade Area of the Americas summit in Québec City the previous April. We ourselves decided to head towards the Red Zone.

That evening, when many people had gathered for social functions, under the cover of darkness and a Mediterranean storm we did our best to gather wooden posts, ropes, iron bars, body armor, and everything else we needed. To this day, I will always remember that rainstorm. The rain was heavy and loud enough for us to carry out everything that we wanted to, but the heat from the local climate created the kind of rain that you could only want more of; it seemed to find its way into every part of your body.

The following day was a relaxed affair: chatting, cooking food, scouting maps, and sunbathing. The first mass demonstration took place that evening, opposing the European Union laws regarding asylum seekers and border controls. It was the first time we would get to estimate how many people were gathered here. We found our way into the menagerie of green, black, and red flags and began our tour of Genoa. The mass of people must have been into six figures, and there was a massive turnout for the anarchist bloc, between 6000 and 8000 participants. The demonstration ended without conflict.

The next morning, I awoke to start making makeshift body armor that would fit beneath my clothes. I used a cut-up sleeping-mat, drainage pipes, and many meters of duck-tape. It wasn’t my intention to have to use it—I was relying on situational awareness and the speed at which I can run—it was more precautionary than anything else. In the future, skating pads and BMX armor are a better solution for this kind of body armor; I did have a bicycle helmet, and many people had invested in motorcycle helmets.

Each affinity group sent one person to a camp meeting. At the meeting, I looked around and put it together that the majority of people who were staying in the campsite intended to participate in the black bloc.

Activists in the Ya Basta/White Overalls bloc march prior to the first confrontations with police.

On the Threshold of the Clash

The following passages are adapted from a forthcoming memoir on PM Press, entitled Ready to Riot: A Chronicle of Anarchist Experiments in Militant Organization & Action, 1995-2010.

“We Are the Birds of the Coming Storm”: Night of July 19, 2001, Albaro Campground

There’s a soothing calm to the night before battle. The knowledge that the time for mobilization, preparation, plotting, scheming, organizing, debating, and worrying is over. It’s a feeling similar to what an athlete experiences before a big game. For better or for worse, in a few hours or a few days, you will know the outcome. You might be victorious or defeated—you might be injured, or, in our case, killed or imprisoned—but you will be on the other side of the event for which you prepared with such dedication and intensity and which simultaneously caused you so much anxiety and excitement. All you can do is hope that you have prepared yourself and your proverbial teammates the best you could, and that you will give the best you have to give when the moment of truth comes.

The setting of this particular night, here in the park, conspires with us to validate what many of us feel. For us, at least at this moment in time, nothing exists outside of the momentous confrontation that is about to take place.

The night is pitch black; there are no stars in the sky above us. In the darkness, under the cover of pouring rain, one can make out the shadows of dozens of black-clad figures laboring intensely. We hear the sounds of metal and wood, hammers and knives, being used with wordless determination.

“…despite the pouring rain, the camp was in full swing preparing for the next day. People tearing up benches, breaking apart poles, fashioning long flag poles, pulling metal bars out of the ground, attaching flags to wooden beams, making Molotov cocktails, and collecting everything that could be of use the next day and storing it for the night. It was clear that the coming days would be intense.”

-“The Black Bloc in Genoa: An Affinity Group’s Account,” Barricada #8, Summer/September 2001

Once satisfied with our own personal preparations, and having lent a helping hand to the comrades in our affinity groups and larger cluster, Oscar, Lena, and I sit down for a moment of well-deserved rest before the storm. We have been facilitating meetings, writing and translating texts, and preparing materially without cease since we arrived in Genoa—not to mention being on the road now for well over a month. Our efforts are in no way extraordinary here; the commitment and dedication of the several hundred people who comprise the core of the movement that Tony Blair derisively referred to as “the anarchist traveling circus” is inspiring and motivating to witness.

Still, though our youth and ideological fanaticism mask this well, underneath them, we are tired.

Scenes following the initial confrontation between Ya Basta / White Overalls and the carabinieri on July 20, 2001.

We seat ourselves around the makeshift fireplace that a few of the Parisian comrades have started, protected from the rain by an awning. Marianthi and Nikos joins us—two Athenian anarchists from a collective that corresponds with our own collective, Barricada. We’ve become closer with them over the course of the past few days. I introduce the Parisians and the Athenians, all of whom are friends of mine, but who do not know each other. Having lived in both France and Greece, I identify strongly with both of these currents of anarchism and their particular regional peculiarities. Both currents fit within the family of revolutionary anarchism; they are generally more or less friendly to each other, but they contrast starkly with each other in terms of political culture, organizational methods, and priorities in day-to-day organizing.

Hearing that the Parisians are from the CNT [the Confédération nationale du travail, a French anarcho-syndicalist union founded in 1946 by Spanish anarcho-syndicalists in exile], Nikos blurts out, “So why are you here?” He means the question in a comradely way, but he is clearly curious.

Julien, never one to turn down the opportunity for a good speech, makes a convincing case for the importance of anarchist workplace organizing, for an anarchism planted firmly in the struggles and daily needs of workers and communities. “That’s the priority of our agitation, and of my work as an anarchist. It’s our bread and butter in the CNT, and what I believe will one day lead us to establish the conditions for a general strike. Of course, I also believe that the anarchist movement needs to be able to communicate through symbolic messages as well. To raise its voice on an international level, to show its internationalist and combative character, and its strength to pierce the veneer of capitalist stability. My priority is not summits, and some in the CNT see them as a distraction, but many of us feel these mobilizations and moments of mass resistance complement our work.”

Nikos and Marianthi nod approvingly. They seem satisfied enough with this answer. In any case, they refrain from the critique of unionism, revolutionary or otherwise, which they might have presented at any other moment. In this case, their motivations are similar enough to Julien’s—and if nothing else, this comradely late-night fireside chat is already illustrative of one of the stated reasons why they are there.

Their own analysis, and that of many Athenian anarchists, is preserved in the text they wrote titled “Genoa Will Not Be Porto Alegre,” which we will publish in our journal, Barricada.

“Because it is a chance to meet with our comrades who will come from all around the world, a chance (…) to promote continual conditions of communication and coordination of our struggle (…) in order to create together moments of social counter attack.”

“Genoa Will Not Be Porto Alegre,” Barricada #8, Summer/September 2001

“We are here to turn these summit into moments of ungovernability and insurrection. So that we send a message of rupture not just with the state, or the cops, or capitalism… but also to all the NGO scum, the Stalinists, the reformists, the authoritarian pacifists, the nationalists. All of those who want to use this movement and this moment of rebellion as a vehicle to become managers of capitalism or to present us with a supposedly better version of it.” Marianthi’s disdain for all of these is so strong it looks like she is about to spit into the fire with disgust as she utters their names. She closes with dramatic flair: “We are here because we need to be wherever revolt happens, and at the same time, we will work to make revolt happen wherever we are, like we do in Athens.”

Lena, Swedish and succinct, says something to the effect of “I’m an antifascist first and foremost. Capitalism is the breeding ground of fascism, so I must fight to eliminate one if I want to exterminate the other. So if the leaders of capitalism are having a party, I will be there to disturb it.” Clear, concise, and to the point. I like it. “I’ve just never been to anything like this before except Gothenburg. That was much smaller, and it was still intense. So I’m curious what will happen tomorrow and what to expect.”

The frontlines of the Ya Basta / White Overalls bloc on the Via Tolemaide.

This is the question on everybody’s minds. “What do you think will happen tomorrow?”

Nikos expresses the minimum expectation that everyone shares. “At the least, we will create chaos and disrupt the veneer of capitalist peace and invincibility. We’ll show them that we are always more and more, and that eventually, no army will be able to protect them or their society.”

The others don’t find his summary of the intermediate expectation too controversial, either. “Maybe we can overrun the red zone, give them the scare of their lives, and delay or even cancel the summit.” Based on what I saw a few months earlier at the mobilization against the Free Trade Area of the Americas ministerial in Quebec City, this doesn’t seem too far-fetched, either. Yes, the carabinieri aren’t exactly the same as Québécois cops, but likewise, the numbers and experience of “our side” in a place like Italy are greater than in Canada.

But when Nikos presents the “maximalist” scenario for the coming days, two distinct camps appear within our little fireside group. “We will generate so many points of conflict, clashes will become so widespread, that the cops will not be able to hold the city. The people here are sympathetic to us and a dynamic of widespread revolt can develop. We won’t just smash and burn the symbols of capitalism—we’ll open the shops and supermarkets, redistribute goods in an organized fashion. The heart of the city will be able to experience a temporary liberation from capitalism and have free access to whatever they need, while tens of thousands of fighters keep out the forces of the state. For a few hours, or days even, we’ll establish the Commune of Genoa.”

If it were socially acceptable, I think the Parisians would laugh out loud at this. Lena, I can’t really judge. The comrade I affectionately refer to as the Old Man glances at me, biting his lip and clearly doing his best to avoid rolling his eyes dismissively. I know what he is thinking: “Great, now this crazy has found a whole nest of similar crazies.” He isn’t wrong. I don’t articulate my aspirations aloud very often; even among anarchists, they are generally viewed as wildly optimistic, not to mention potentially dangerous. But here, I am in the company of a whole scene of anarchists—and a combative and experienced one, at that—who boldly believe that such a scenario is indeed thinkable.

I can tell that the Old Man is worried about us wildly overestimating both our support and our material strength. He is probably also rightfully outraged about how crude our revolutionary strategy seems to be. He often says as much. “Who needs revolutionary thinkers and analysis when we have you geniuses?” he quips when he catches us advocating for a strategy that boils down to “Whatever, just push until it falls.” If he were to say something right now, I’m sure it would begin “Oh great, now it’s ‘push until it falls at least in a small place and for a few hours.’ Another great leap forward in revolutionary strategy and theory.”

Taking advantage of the lull in the conversation, Lena declares, “It’s late and I’m going to sleep. You should all probably do the same.” Everyone takes her cue without argument. We say our goodnights with powerful hugs. The unspoken message is clear: “I’ll be at your side tomorrow. I’ll protect you if you fall, I’ll care for you if you are injured. We’ll advance as one and retreat as one. Together, we’ll make history.” This unlikely and eclectic group of people from the farthest corners of the world—Parisian anarcho-syndicalists, Athenian insurrectionists, a Swedish anti-fascist, a Chilean ultra-leftist, and one Argentine anarchist crazy—have become a family. And we haven’t even entered battle together yet.

The entire camp is asleep. As we quietly push open the door to the gym, we are greeted by the wholesome sight of hundreds of people spread out over every inch of the floor, sleeping placidly. Hundreds and hundreds of anarchists. In a few short hours, we will fight some of the most intense battles against the police that Italy and Europe have seen in years. We too enter the gym and quickly fall fast asleep, nestled comfortably in each other’s arms and surrounded by a few hundred of our closest friends.

The demonstrations in Genoa represented the high-water mark of an era of global protest.

The Golden Horde: July 20, 2001

We’ve just finished the short descent from campground to street level, down the narrowest of stairways etched windingly into a typical Genovese cliff. Wide enough only for three people abreast, our little international cluster of fifty or so people leads the way. We are the first to reach the street. There are maybe fifteen or twenty Athenian anarchists, ten or so of the Parisian CNT and Brigada Flores Magon crew, a few German and Swedish autonome antifas, some Eastern European comrades from “Abolishing the Borders from Below,”2 and, of course, the “Barricada and friends” crew.

Looking around at the masked and helmeted yet nonetheless familiar faces around me, I realize that I would feel safer riding into battle with these fifty than with any five hundred strangers dressed in black. In some cases, this is based on personal experience—in other cases, it is because their reputations precede them—but I know that those around me represent some of the most committed, experienced, and combative exponents of modern-day anarchism from around Europe and North America. Swedish anti-fascists from the Anti-Fascist Action network who are not only unfazed by the events in Gothenburg and the subsequent repression, but galvanized by them. Parisian CNT members with a general strike behind them. The ex-Red Warriors and Brigada Flores Magon crew with over a decade of successes fighting fascists. Athenian comrades, many of them veterans of the November 17, 1995 Polytechnic occupation, the riots that greeted President Clinton’s visit to Athens in 1999, as well as the mobilization against the meeting of the International Monetary Fund in Prague the previous year. It is a veritable who’s who of revolutionary anarchism—and that’s just in our cluster of fifty or so.

As I turn to look back at the stairway behind us, I see an image that is a poem. A militant poem. An exercise in mass militant poetry. Artists may put their poetry on a piece of paper or on a canvas, but the poetry of revolutionary struggle is exclusively three-dimensional. It lives, breathes, and moves before your eyes. Fleeting by nature, it is difficult to evoke after the fact. We experience art and poetry that can only be appreciated by the protagonists and perhaps those fortunate enough to bear witness to these moments.

The perfect blue of the late morning summer sky offers a backdrop to the dramatic cliff into which the narrow winding staircase is etched. Today, the staircase is packed from top to bottom with black-clad combatants radiating passion, conviction, and emotion. The first roars of “No nation! No border! Fight law and order!” echo through the city of Genoa.

We might not be the Golden Horde3 of Nanni Balestrini’s 1970s Italy, when an entire generation of rebel workers defied the state, parties, and bureaucratic unions to create beautiful scenes in which thousands spilled out of the factories to take on the police and the society they defend. But for today, we are the equivalent—the Golden Horde of international anarchism. Thousands upon thousands of us have dedicated our time, our minds, and our bodies to articulating a wholesale rejection of the existing order. We have come, if not from all corners of the world, at least from all corners of Europe and North and South America, to take on the capitalist rulers of this world and their private army of almost twenty thousand police officers.

In the future, the question of whether this is a strategically sound course of action will be the subject of heated debate. But in this moment, it matters next to nothing. What matters is expressed in the first sounds of breaking glass and the Molotovs flying through the air to greet the first cops on the horizon. The time for talking is over. We have declared that we will wage war—our war, the social war—against capital, the state, and all forms of domination.

It’s time to make total destroy.

Make Total Destroy: July 20, 2001

The following passage is drawn from an account that appeared in issue #8 of the Boston-based journal Barricada in September 2001.

After four days of meetings, it was decided that on July 20, we would meet up and march with COBAS [Confederazione dei Comitati di Base, a rank-and-file trade union]. Those who were staying at the Albaro camp would meet at 10 am the next morning and join the COBAS march as it passed by at 10:30 am, convening with other Black Bloc’ers at 12 pm at the Piaza Paolo da Novi.

Hundreds had assembled with their materials towards the back of the park; 10:30 am came and went, but we saw no march. News came in that the march had been delayed by police and that police were attacking the social center Immensa, tying up some 300 comrades outside the city. After a bit of arguing, as it became clear that the march was not coming, we decided to depart on our own.

Despite a few minor directional confusions, we arrived at the meeting point, finding a sea of red COBAS flags and other masked comrades.

As we marched in, swelling in numbers, some began to attack targets representing capitalism. While people were thoroughly destroying a bank, police came in from the right. People staged a brief offensive involving a few Molotov cocktails and stones; the police deployed tear gas and charged. As a result, one section of the black bloc, numbering around 500 people, was pushed towards the sea, while another much larger section, consisting of probably at least two thousand people, was pushed north into the city.

A map of Genoa during the G8, indicating the red and yellow zones and some of the events: 1) Palazzo Ducale, where the G8 summit took place; 2-6) Genoa Social Forum (GSF) meetings points—piazza Portello, piazza Manin, piazza Dante, piazza Paolo da Novi, and Boccadasse, respectively; 7) endpoint of the sindacati di base demonstration; 8) starting point of the Tute Bianche demonstration; 9) GSF convergence center; 12) temporary housing for police forces; 13) police headquarters; 14) piazza delle Americhe, where the Tute Bianche demonstration was supposed to end; 15) at the Via Tolemaide intersection, carabinieri forces stopped and attacked the Tute Bianche demonstration; 16) police anti riot-units led by Pagliazzo Bonanno attacked the Lilliput Net pacifists in piazza Manin; 17) piazza Giusti, where the “DìxDì” supermarket was attacked; 18) the Marassi prison, which the black bloc attacked; 19) piazza Alimonda, where Carlo Giuliani was killed; 20: corso Gastaldi e via Tolemaide, where an additional police attack took place.

The bloc on the south, towards the sea, began to assemble barricades out of dumpsters, wood, and whatever other materials were available. Fires were started in some of the dumpsters. In the meantime, others continued to target the faces of capitalism, such as an abundance of banks and gas stations. Desks, chairs, computers, and other materials from the banks were pulled out and added to the barricades. Soon, the police charged again, leading to a brief confrontation, an attempted charge involving about five people from the bloc, and then yet another retreat towards the sea. This process continued for about an hour until the bloc was finally pushed to the street right in front of the GSF convergence center—a parking lot immediately up against the edge of the sea.

There, thanks to some flaming barricades, people were able to regroup and attack some more banks as well as a car dealership. One main bank was set on fire. The situation facing the bloc was grim, to say the least. Facing into the city from the waterfront, to the sharpest right, there was a steep staircase leading up into city neighborhoods. To the more gradual right, the main road we were on led towards the COBAS camp, Albaro, and the fortified police station. Straight ahead were the barricades, and to the left was the central police headquarters—with trucks, vans, tanks, and the like. On all sides there were carabinieris.

This location was secured for about half an hour; during this time, more banks were destroyed, along with a Lufthansa office, which was decorated with the slogan “Stop Deportation.” Eventually, the police charged once more, deploying heavy amounts of tear gas, forcing everyone to retreat into the GSF convergence center, black bloc and COBAS alike. Immediately, everybody—regardless of political or tactical preferences—began barricading the entrances to the 12-foot-high fences that lined the convergence center.

For about one hour, nearly one thousand people inside the convergence center lined the fence, throwing rocks at the police in the distance and firing slingshots. At this point, most people began to migrate to the back of the parking lot, along the rocks of the sea and out the other end of the convergence center, further down the road, in the direction of the COBAS camp, which was already past the riot police barricade on that side. About 500 black bloc’ers and people mobilized by COBAS were left. They marched together in the direction of the COBAS campground. When the march reached the police station, people threw rocks at the windows, destroyed the security cameras, and spray-painted the walls. About a block past the police station, a faction of COBAS began blocking the street, refusing to let the bloc pass. This essentially left us trapped between them, the sea, and the police station.

Needless to say, this generated fighting between the groups, as these COBAS militants were violating all principles of solidarity in effectively attempting to sacrifice the bloc (which now consisted of no more than 200 people) to the police. After about 20 minutes of confrontation and sporadic fighting, they stepped back and allowed the bloc to pass.

At this point, most of the remaining participants in the black bloc decided to change and disperse in order to reach other areas of the city where the possibilities for action were greater.

While all this was occurring, the large bloc that had headed north, which eventually swelled to over three thousand people, marched through the city for several hours, destroying all the symbols of capitalism in its path—from banks and luxury cars to chain-store supermarkets. People began to set up barricades to block the police from accessing the entire area of the bloc’s activity. Some stayed behind to defend these barricades, while others split into two main groups. One of these groups headed to attack a prison, and another in the direction of the red zone.

Demonstrators forced carabinieri to flee an armored vehicle, which was then set on fire.

Those who headed to attack the prison were able to chase away the few riot police stationed there and to inflict substantial damage on the administrative building of the prison via Molotov cocktails. Eventually, however, riot police came in from behind and forced them to retreat to the area of the “White Hands” pacifists. The situation with these authoritarian moralists quickly became unbearable and the bloc dispersed to look for more suitable areas of action.

Those who headed to attack the red zone, eventually joined by many of those who had headed for the prison, ended up engaged in a massive confrontation with hundreds of carabinieri under and in front of a tunnel that led to the general area of the red zone. During this battle, a situation arose similar to the one in which a police officer murdered Carlo Giuliani, as carabinieri used their vehicles to charge the black bloc barricades. People met these attacks with energetic resistance; one police vehicle was cut off from the group and attacked. A police officer used his firearm, but fortunately, in this case, he fired into the air.

After this battle, the bloc once again began to disperse into many smaller groups. Together, black bloc’ers and local residents raided and looted a supermarket; barricades were erected virtually everywhere.

Not far from all this, the Ya Basta! bloc was engaging the police. However, as soon as the situation escalated from spectacle to real confrontation, Ya Basta! chose to retreat, despite being very well-equipped. Fortunately, many of the rank-and-file participants were quick to disobey, rightfully outraged at the police violence, the attitudes of the Ya Basta! elders, and the murder of Carlo Giuliani, which had just taken place in another clash with police. They continued fighting alongside black bloc elements and some very angry locals.

Black bloc and “discontents” from the White Overalls bloc erect barricades and clash with carabinieri.

Another View: The Confrontations of July 20

This passage is adapted from the aforementioned issue of the hardcore zine Inside Front.

After some delay, we left the camp en masse. We were amazed that this many people dressed in black did not draw police attention. As we descended into the town, calls of “No justice, no peace! Fuck the police!” rang from the streets. Once in the town center, we realized that there was very little continuity anywhere, no organized marches that we could join—there was just a mass of people, and the only conclusion was that there was already a riot in full flow. This was damaging to our plans, but there was nothing we could do—and perhaps people had already started attacking the cops?

To make sure that our affinity group would not get separated, we had designated a word that we would call out if we all needed to come together. It’s best to use an uncommon word for this purpose; for example, we used the word “Moose.” At this point, the section of the black bloc that I was in got split up; once we regained our bearings, we decided to make our way towards the red zone. With us, we had a black bloc marching band and many affinity groups.

The sun was hot and unrelenting. I was drinking water faster than I could find it, and all the shops were shut. What is the alternative to shopping? Looting. We came across a supermarket, and the next thing you know, people were trying to pull off the door shutters. Eventually they came off, and we had the whole shop to ourselves. I ran in and got as many cartons of fruit juice as possible, along with bags of chips and other light snack foods. The sprinkler system triggered itself, reducing visibility; as I was running out, I tripped on an abandoned cash register, injuring my right foot.

Thus refreshed, our affinity group conferred. We decided to remove our black clothing and find a quicker route to the red zone.

We made our way to a park square, where summer bands were playing, people were drinking Italian wine, and children were playing. We sat and calmed ourselves in the peace for a much-needed breather.

Hoping to find out what was going on, I wandered back into the street. There, I met another affinity group; one of them reported, “The prison is being trashed and a fragment of the black bloc will be here soon.” With that news, we all shifted back into our other identity.

It was not a moment too soon. I looked to my left and saw a phalanx of riot cops, just before they tear-gassed the whole area without hesitation. At this point, it was too late to put on my gas mask, but nor could I retreat to find clean air, as in front of me there were children as young as five years old screaming, crying, and panicking. I did my best to get them behind us and to clear the area of tear gas canisters. The gas was overwhelming.

Once the children were safe, I ran in what I perceived to be a “safe” direction. At this point I couldn’t breathe, see, or think—all I could make out was the shape of one of the members of our affinity group. Luckily, he was twice my size—he picked me up after I called his name and he flushed the gas from my face, eyes, throat. We were safe for the time being, and all of us were furious about the disregard that the cops showed for the well-being of the children who were in the area. In my mind, I declared myself in a state of war.

We decided to head into the city center to join whatever was going on there. Genoa is a hilly city, so we could see across the horizon and see tear gas, black smoke billowing into the sky above, and also the continuous firing of ‘anti-riot weapons’ by the Italian police. We eventually found ourselves next to a train station, where the highway had what looked like thousands upon thousands of people on it. We headed into the crowd gingerly, as we were expecting hostility on account of our dress code, but there was no conflict.

I knew a British friend of mine would be in Genoa, but I had no idea where he would be, and as I was walking in the road, I heard someone call my name. It was my friend. I was wearing a mask, sunglasses, and baseball cap and he still recognized me! I got to chatting with him and he took us closer to the “front line.” We equipped ourselves and I put on my gas mask, saying to myself, it’s now or never. One of the most significant moments, for me, was seeing how many people were suffering the effects of tear-gas but not knowing what to do—some were ignoring it, some were washing water straight into their eyes, and others were using a lemon juice solution! I saw a middle-aged man who was in a bad way, his eyes horribly swollen. I approached to assist him. I was anticipating daggers, but he was very warm and welcomed my assistance, considering that I was dressed the way I was and had a full face gas-mask on. We connected. He thanked me in his best English. When I waved goodbye, he raised his fist and smiled.

Down at the front line, many people were dodging the “mortar bomb” tear gas grenades. I’ve never seen anything like them. When they landed, they deposited a very dense gas, but they didn’t get hot and were easy to handle. The cops witnessed how easy it was for us to throw them back. Consequently, rather than launching them at a 45-degree angle, the way that tear gas canisters are supposedly designed to be used, they chose to fire them directly at our heads. If you were hit by one of these, the effects could be life-threatening.

We gathered as much ammunition as we could from crumbling walls and pavements, and began disposing of them towards the cops. Things were at a stalemate, with no one moving back or forward. We assisted each other in dodging the large tear gas canisters, and we began to hold the cops at bay. Some of us looked around to see if there was anything that we could build barricades out of, but there was nothing.

I went back into the crowd and met members of my affinity group, refreshing myself on chocolate and water. The heat of the day was unforgiving. We went back as a group and found that momentum had built up on our side: we were pushing the cops back at such a rate that we were able to pick up the stones that we had previously thrown. A supermarket trolley was adopted to transport stones.

Things were going well and at a very fast pace. I felt no angst, no remorse, no sadness—I was so focused on the job at hand of watching the air for missiles, trying to breathe in the gas mask, and monitoring police movements that the whole event was a continuous series of explosive instants. The foot that I had damaged earlier was the bane of my day; eventually, I had to rest. I sat down on a doorstep on the side of the street and waited to regain my energy. It wasn’t a moment too soon.

I was jogging back to the frontline when my ears were subjected to a mechanical screaming—there was an armored vehicle driving straight into the crowd of people. People ran. I ran. I looked across the road and saw cops running alongside it, hitting and pummeling anyone they could, while in the other lane a water cannon was doing its best to knock down those who were running away. I turned around and saw the nozzle of another water cannon pointing at me—I tried dodging it, running in a zigzag, but it was too late, the next thing I knew I was been blown across the road like a tumbleweed into a crowd of people. I got up and managed to get back into running. A woman fell flat on her face in front of me. I helped her to her feet and saw an expression of terror on her face.

Black bloc and demonstrators from the White Overalls bloc begin to merge as clashes multiply across the city.

There was so much tear gas in the air that you couldn’t even work out what direction was best to go in. I lost my affinity group and found myself on my own. I darted up a narrow street and did my best to get out of my soaking wet, tear-gas-covered clothes while getting my breath back. A group of people gave me water and carried my rucksack while I gathered my mind, strength, and energy. They were extremely accommodating and helped me go through all the back streets to return to where we were camping. I thank them to this day.

All I could do now was to wait for my friends to get back. While I waited, I heard many different rumors, and one of them turned out to be true. The police had murdered Carlo Giuliani, another demonstrator like myself. It haunted me; it still haunts me today. I later learned that the street battle we participated in was immediately adjacent to the scene of Carlo’s death.

Eventually, my friends arrived back as smaller groups or individually. Then, like a sudden storm, another rumor. We hear that the GSF had held a press conference for the Italian Media, and that they were reported to have said something along the lines of “…the violence today can be solely blamed on the anarchists, the violent majority of whom can be found…” in the campsite where we were staying.

We concluded that we should sleep somewhere else that night.

“Who are you calling ‘outside agitator’?”

July 21: The Fight Continues

The following passage is drawn from the aforementioned account in issue #8 of Barricada, September 2001.

This was to be the day of the offensive attacking the “red zone.” Many estimated that ten thousand people would break from the march and attack the red zone, but the question remained as to how they would all assemble into one large bloc. Many simply decided that, rather than marching out of the city simply to march back in, it would be best to wait at the convergence center and assemble people there.

At around 2 pm, the first parts of the seemingly endless march began to pass into the city, turning north upon reaching the convergence center. Eventually, people began to head straight towards the police headquarters rather than turning north. People re-entered the banks that had been attacked on the first day and collected materials for barricades. Another group moved a car into the street and flipped it, eventually setting it on fire.

The line of approximately 100 riot cops deployed gas continuously, forcing a large part of the attackers back due to lack of equipment. The attackers likely numbered at least two thousand. Fortunately, the police advance was slowed by the burning car and barricades.

Anarchists and other revolutionaries clash with thousands of cops on July 21.

Subsequently, many people headed up a large avenue north into the city. Three more banks were destroyed. At one point, a line of carabinieri came flying around a corner, sending many running in all directions. The pacifists began refusing many people entry into the large march once again, effectively delivering them to the police. This led to some insults in both directions—”This movement doesn’t need you,” “you are all cops,” and a wide range of slurs—and some confrontations.

The march continued. A smaller bloc of about 300 people formed towards the back, and small clashes continued with the police lines advancing behind them. The march passed under three bridges, the same location that had seen the massive confrontation on the previous day. On the other side of the tunnels, the bloc decided to barricade the area to delay the advancing police. People smashed the bank windows on one side of the street and pulled off the protective plywood on the main door and windows. They pushed the plywood and dumpsters to block each of the three exits from the tunnels under the bridge. They entered the bank and added boxes, carts, desks, and everything else inside to the barricades.

Some people attempted to push the barricades further into the tunnel. In the process, a group tipped a car over and added it to the middle tunnel exit. While this was taking place, another portion of the bloc was collecting loose cobblestones and bricks from the courtyard next to the bank and stacking them neatly behind the barricades. As soon as the barricades were prepared, people set them on fire, and added loose papers and cardboard from the bank to keep the fire burning.

The bloc continued heading north, systematically attacking every bank and gas station. It soon became clear that the police had either gone around the tunnel barricades or broken through them, as tear gas clouds could be seen emerging from that area. Many headed back to find others waging a pitched battle with police on a diagonal street one block north of the tunnel.

For the rest of the day, small black bloc groups engaged in confrontations throughout the city, and many others joined them. The concerted attack on the red zone that people had anticipated never took place, as the police acted strategically, constantly dividing and dispersing focal points of confrontation.

Afterwards, a quick tour of the city revealed astonishing amounts of property damage, as well as several charred police vehicles.

July 21: The Raid on the Diaz School and the Indymedia Center

The following account originally appeared in Recipes for Disaster, our “anarchist cookbook” of direct action skills and tactics.

Following a heavy day of rioting and police brutality, in which demonstrator Carlo Giuliani was shot and killed, I headed back to the Indymedia Center (IMC) in the Diaz School.

After the shooting, the tension was rising, along with paranoia about police repression. People began to leave both the Indymedia Center and Genoa. There was much discussion about what to do, but no firm consensus was reached. Many people made the decision to leave independently, to such an extent that at the Indymedia Center our numbers were cut in half as the night wore on. More reports of police movements came in. Some protesters threw stones at a police car outside the IMC, which only heightened the tension and paranoia. We held a meeting to try to decide what to do with the video material and with ourselves if the police did raid, but came to no conclusion. Maria and I decided on our own emergency plan: we would hide out on the roof in a water tower.

At midnight, there were shouts that police were coming. I looked out the window and was unable to see anything, but people started running around grabbing things and barricading doors. I ran to find Maria and reminded her about the hiding place on the roof I had checked out earlier. She grabbed the tapes and equipment and headed to the hiding place. Looking out a window, I could not see any police around the front door, so I shouted this information to the people blockading the door.

I went up to the roof and filmed the carabinieri (Italian police) breaking into the school building opposite our building. Things were getting out of hand across the street: a police van smashed through the front gate and the police began breaking windows with chairs and smashing down the doors with tables they found in the courtyard. Worried for my safety and for the safety of the video I had just recorded, I decided to head back downstairs to see if the police were coming after those of us in the IMC building as well.

Everything seemed calm down at the IMC. I wondered whether the police were going to invade this building. I decided to go further down and check. After two flights of stairs, I turned a corner and came face to face with a policeman dressed in full body armor, his truncheon drawn, panting his way up the stairwell. I turned and flew up two flights shouting, “They are in the building!” I scrambled past the barricaded door to the IMC and up to the roof. Dodging the spotlight from the circling helicopter, I headed over to the window looking upon the water tower and lowered myself out, whispering, “Maria, it’s me.” No answer. Creeping in the darkness to the water tower, using only the infrared beam of my camera to light my path, I made my way down through the corridor of water tanks. I kept whispering “Maria, are you there,” and started to panic that she was not. A small and frightened voice finally said back to me, “Turn that light off.” She was hiding in the space behind the last water tank.

We waited. She had brought a bottle of water and supplies. We talked about what we would do if the police came to our hiding place in the water tower. Would they come in and search? Would they throw tear gas in? Would they smash our equipment and break our bones? All of these possibilities were very real. Meanwhile, the helicopter circled very low, its spotlight lighting up the water tower, the propellers shaking the building.

The screaming went for what seemed like hours. Maria remembers, “I was sure there were people being murdered. It was not just screaming in pain, it was screaming in fear of death. So I sat there waiting for my turn to scream. Then the noises mingled into a frantic, maddening mixture of screams of fear, shouting of angry cries of “Assassini,” ambulance sirens, and helicopter motors just above our heads. Suddenly, we heard noises of movement outside. Police were searching the roof. We kept very quiet and still for nearly four hours. When the helicopter finally disappeared, we dared to exit the water tower.”

We met other survivors of the raid wandering across the rooftop in a daze. Grabbing our camera, we interviewed two English girls who had been in the Indymedia Center during the raid. Then we headed downstairs to survey the damage: doors smashed open, computers dismembered, hard drives ripped out, monitors smashed.

Across the street, much worse was waiting. Blood covered the floor, congealing in puddles and sprayed upon walls. Trails of blood led into corners, clothes lay around in disarray, personal belongings covered the floor specked with bloodstains. Dazed people were searching through the piles as local reporters stood together in clumps. Up the stairs, bits of skin and clumps of hair stuck to the walls along a trail of broken doors and hasty barricades. The police had ransacked cupboards and overturned desks, searching all the places where someone could have hidden. Heads had been bashed against walls and the smeared bloody handprints left a distinct smell in the building. The carabinieri had left their mark.

We escaped with the footage of it all, and it spread all over the world.

Some footage from the police raid on the Diaz school. Viewer discretion is advised, as these scenes show the consequences of nearly lethal police violence.

Afterwards

This passage is adapted from the aforementioned issue of Inside Front.

After walking for many hours, we arrived at a small Italian beach town, and the waves beckoned us. I hadn’t washed in over a week—unless you count the water cannon—and I had soaked up quite a bit of tear gas.

The water was so refreshing. To swim amongst the crashing waves was a stark contrast to the whole week’s worth of events.

We got on a train heading out of Italy to the Mediterranean coast of France. We were exhausted. I felt good, but my mind had been overworked. Still, deep down, between the pain and angst, I knew that the whole experience had given me the feeling that the risks we took were worthwhile. We fought for our lives, and our desires defended.

Against incredible odds, the demonstrations in Genoa showed that it was possible to beat the police, even at their strongest.

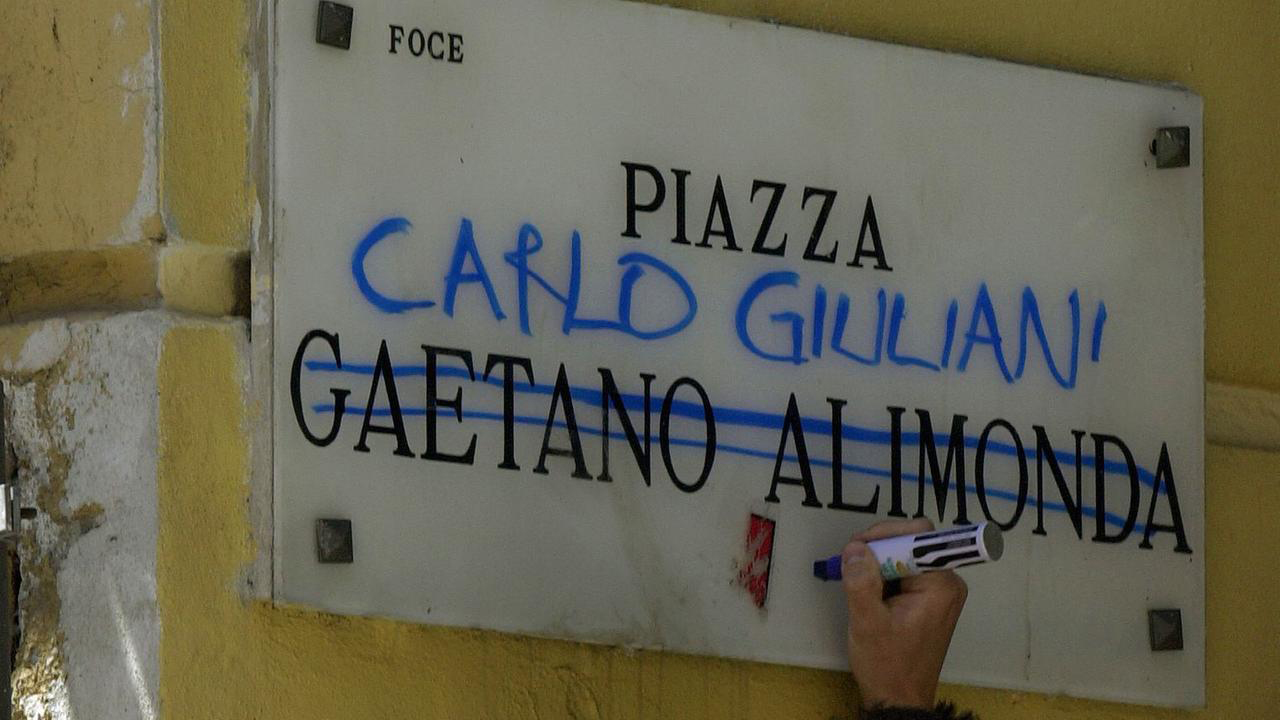

Appendix: We Remember Carlo Giuliani

After the murder of Carlo Giuliani, murals in his memory appeared around the world.

Mourners have informally renamed the street on which Giuliani was murdered in his honor.

Graffiti remembering Carlo Giuliani in Piazza Vetra, Milan, Italy.

A park named for Carlo Giuliani in the Kreuzberg neighborhood of Berlin.

Carlo Giuliani Park in Berlin.

A mural in Saint Louis, Missouri, painted immediately after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, memorializing Carlo Giuliani, among others.

https://twitter.com/VIM_Media/status/1285852476550217728

A song for Carlo Giuliani.

The flower of rebellion

Was trampled by men in uniforms

Crushed and left on the ground

The wind blew it away

But the flower of rebellion

Has a seed that has flown away

And in some other beautiful land

One day it will bloom again.

Further Reading and Viewing

- Testimony of an Anarchist on the Events of Friday, July 20, 2001 in Genoa—An important historical document produced immediately after the events, this account corroborates much of the narrative above; it also includes firsthand testimony about the murder of Carlo Giuliani (in French)

- On Fire: The Battle of Genoa and the Anti-Capitalist Movement—A book collecting accounts and reflections from the 2001 G8 protests in Genoa

- “Staying on the Streets”—Starhawk’s reflections after the G8 in Genoa

- Where is the Festival? Notes on Summits & Counter-Summits

- The Anarchist Ethic in the Age of the Anti-Globalization Movement

- Reflections—and a Tour—20 Years after the Death of Carlo Giuliani

- Ordre Public Gênes—A French-language documentary about the events in Genoa

22 Years of Counter-Summit Mobilizations

- Flashback to June 18, 1999: The Carnival against Capital

- The Power is Running: Shutting Down the WTO Summit in Seattle, 1999

- The Québec City FTAA Summit, April 2001: The Revolutionary Anti-Capitalist Offensive

- Let Me Light My Cigarette on Your Burning Blockade: An Eyewitness Account of the 2003 Anti-G8 Demonstrations in Évian, France

- Taking on the G8 in Scotland, July 2005: A Retrospective

- Can’t Stop the Chaos: Autonomous Resistance to the 2007 G8 in Germany

- The Pittsburgh G20 Mobilization, 2009—see also this account

- The Toronto G20, 2010: Eyewitness Report

- DON’T TRY TO BREAK US–WE’LL EXPLODE: The 2017 G20 and the Battle of Hamburg

-

In the expressive words of Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) leader Subcomandante Marcos, “I shit on all the revolutionary vanguards of this planet.” ↩

-

Abolishing The Borders From Below was a bi-monthly anarchist magazine published by a Berlin-based collective since 2001, involving a handful of Eastern European and ex-Soviet migrant anarchists, packed with news and analysis from correspondents all around Eastern Europe. ↩

-

The Golden Horde is the title of Nanni Balestrini’s definitive work on Italian revolutionary movements of the 1960s and 1970s. Balestrini himself was a co-founder of “Potere Operaio” and a supporter of the influential ultra-left grouping “Autonomia Operaia.” Accused of membership in a guerrilla organization in 1979, he escaped to France. As a novelist, he is best known for his 1971 novel about labor struggles at the Fiat factory in Milan, Vogliamo Tutto (We Want Everything), which this author highly recommends. ↩