I. Normalcy

People from the (rapidly splintering) “mainstream” of society in Europe and the United States today take a peculiar pleasure in considering themselves “normal” in comparison to legal offenders, political radicals, and other members of social outgroups. They treat this “normalcy” as if it is an indication of mental health and moral righteousness, regarding the “others” with a mixture of pity and disgust. But if we consult history, we can see that the conditions and patterns of human life have changed so much in the past two centuries that it is impossible to speak of any lifestyle available to human beings today as being “normal” in the natural sense, as being a lifestyle for which we adapted over many generations. Of the lifestyles from which a young woman growing up in the West today can choose, none are anything like the ones for which her ancestors were prepared by centuries of natural selection and evolution.

It is more likely that the “normalcy” that these people hold so dear is rather the feelings of normalcy that result from conformity to a standard. Being surrounded by others who behave the same way, who are conditioned to the same routines and expectations, is comforting because it reinforces the idea that one is pursuing the right course: if a great many people make the same decisions and live according to the same customs, then these decisions and customs must be the right ones.

But the mere fact that a number of people live and act in a certain way does not make it any more likely that this way of living is the one that will bring them the most happiness. Besides, the lifestyles associated with the American and European “mainstream” (if such a thing truly exists) were not exactly consciously chosen as the best possible ones by those who pursue them; rather, they came to be suddenly, as the results of technological and cultural upheavals. Once the peoples of Europe, the United States, and the world realize that there is nothing necessarily “normal” about their “normal life,” they can begin to ask themselves the first and most important question of the next century: Are there ways of thinking, acting, and living that might be more satisfying and exciting than the ways we think, act, and live today?

II. Transformation

If the accumulated knowledge of Western civilization has anything of value to offer us at this point, it is an awareness of just how much is possible when it comes to human life. Our otherwise foolish scholars of history and sociology and anthropology can at least show us this one thing: that human beings have lived in a thousand different kinds of societies, with ten thousand different tables of values, ten thousand different relationships to each other and the world around them, ten thousand different conceptions of self. A little traveling can still show you the same thing, if you get there before Coca-Cola has had too much of a head start.

That’s why I can’t help but scoff when someone refers to “human nature,” invariably in the course of excusing himself for a miserable resignation to our supposed fate. Don’t you realize we share a common ancestor with sea urchins? If differing environments can make these distant cousins of ours so very distant from us, how much more possible must small changes in ourselves and our interactions be! If there is anything lacking (and there sorely, sorely is, most will admit) in our lives, anything unnecessarily tragic or meaningless in them, any corner of happiness that we have not yet thoroughly explored, then all that is needed is for us to alter our environments accordingly. “If you want to change the world, you first must change yourself,” the saying goes; we have learned that the opposite is true.

And there is another valuable discovery our species has made, albeit the hard way: we are capable of absolutely transforming environments. The place you lie, sit, or stand reading this was probably altogether different a hundred years ago, not to mention two thousand years ago; and almost all of those changes were brought about by human beings. We have completely remade our world in the past few centuries, changing life for almost every kind of plant and animal, ourselves most of all. It only remains for us to experiment with executing (or, for that matter, not executing) these changes intentionally, in accordance with our needs and desires, rather than at the mercy of irrational, inhuman forces like competition, superstition, routine.

Once we realize this, we can claim a new destiny for ourselves, both individually and collectively. No longer will we be buffeted about by powers that seem beyond our control; instead, in this exploration of ourselves through the creation of new environments, we will learn all that we can be. This path will take us out of the world as we know it, far beyond the farthest horizons we can see from here. We will become artists of the grandest kind, painting with desire as a medium, deliberately creating and recreating ourselves—becoming, ourselves, our own greatest work.

To accomplish this, we’ll need to learn how to coexist and collaborate successfully: to see just how interconnected all our lives are, and finally learn to live with that in mind. Until this becomes possible, each of us will not only be denied the vast potential of her fellows, but her own potential as well; for we all make together the world that each of us must live in and be made by. The other thing that is lacking is the knowledge of our own desires. Desire is a slippery thing, amoebic and difficult to pin down, let alone keep up with. If we’re going to make a destiny out of the pursuit and transformation of desire, we first must find ways to discover and release our loves and lusts. For this, not enough experience and adventure could ever suffice. So the makers of this new world must be more generous and more greedy than any who have come before: more generous with each other, and more greedy for life!

III. Utopia

Even from here, I can taste the question already on the tip of your tongue: isn’t this utopian?

Well, of course it is. You know what everyone’s greatest fear is? It is that all the dreams we have, all the crazy ideas and aspirations, all the impossible romantic longings and utopian visions can come true, that the world can grant our wishes. People spend their lives doing everything in their power to fend off that possibility: they beat themselves up with every kind of insecurity, sabotage their own efforts, undermine love affairs and cry sour grapes before the world even has a chance to defeat them… because no weight could be heavier to bear than the possibility that everything we want is possible. If that is true, then there really are things at stake in this life, things to be truly won or lost. Nothing could be more heartbreaking than to fail when such success is actually possible, so we do everything we can to avoid trying in the first place, to avoid having to try.

For if there is even the slightest possibility that our hearts’ desires could be realized, then of course the only thing that makes sense is to throw ourselves entirely into their pursuit and risk that heartbreak. Despair and nihilism seem safer, projecting our hopelessness onto the cosmos as an excuse for not even trying. So we remain, clutching our resignation, as secure as corpses in coffins (“better safe and sorry”)… but this still cannot ward off that dreadful possibility. Thus in our hopeless flight from the real tragedy of the world, we only heap upon ourselves false tragedy, unnecessary tragedy, as well.

Perhaps this world will never conform perfectly to our needs—people will always die before they are ready, perfect relationships will end in ruins, adventures will end in catastrophe and beautiful moments be forgotten. But what breaks my heart is the way we flee from those inevitable truths into the arms of more horrible things. It may be true that every man is lost in a universe that is fundamentally indifferent to him, locked forever in a terrifying solitude—but it doesn’t have to be true that some people starve while others destroy food or leave fertile farms untilled. It doesn’t have to be true that men and women waste their lives away working to serve the hollow greed of a few rich men, just to survive. It doesn’t have to be that we never dare to tell each other what we really want, to share ourselves honestly, to use our talents and capabilities to make life more bearable, let alone more beautiful. That’s unnecessary tragedy, stupid tragedy, pathetic and pointless. It’s not even utopian to demand that we put an end to farces like these.

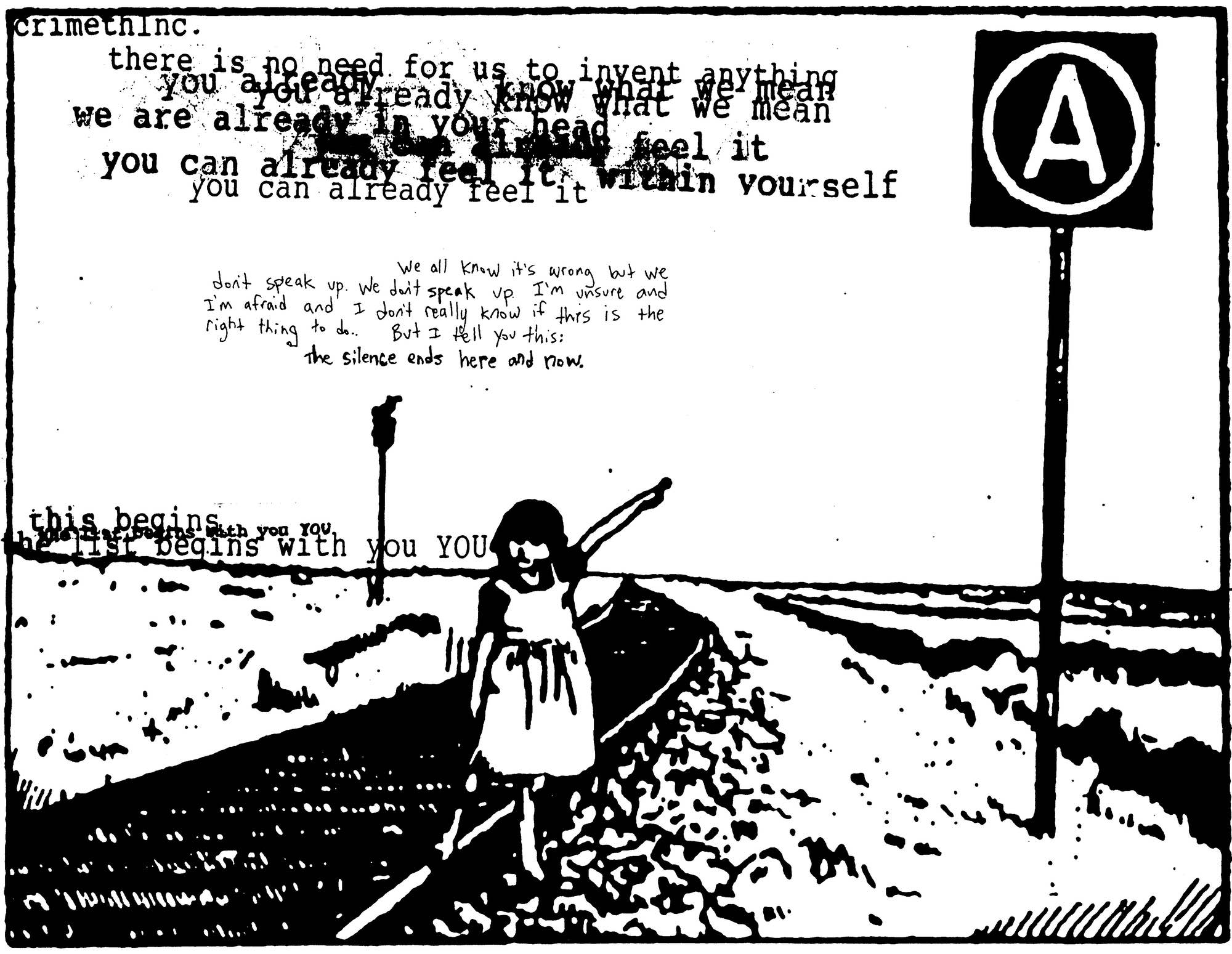

If we could bring ourselves to believe, to really feel, the possibility that we are invincible and can accomplish whatever we want in this world, it wouldn’t seem out of our reach at all to correct such absurdities. What I am begging you to do here is not to put faith in the impossible, but have the courage to face that terrible possibility that our lives really are in our own hands, and to act accordingly: to not settle for every misery fate and humanity have heaped upon us, but to push back, to see which ones can be shaken off. Nothing could be more tragic, and more ridiculous, than to live out a whole life in reach of heaven without ever stretching out your arms.

— by NietzsChe Guevara